Venturing into a little-known fjord

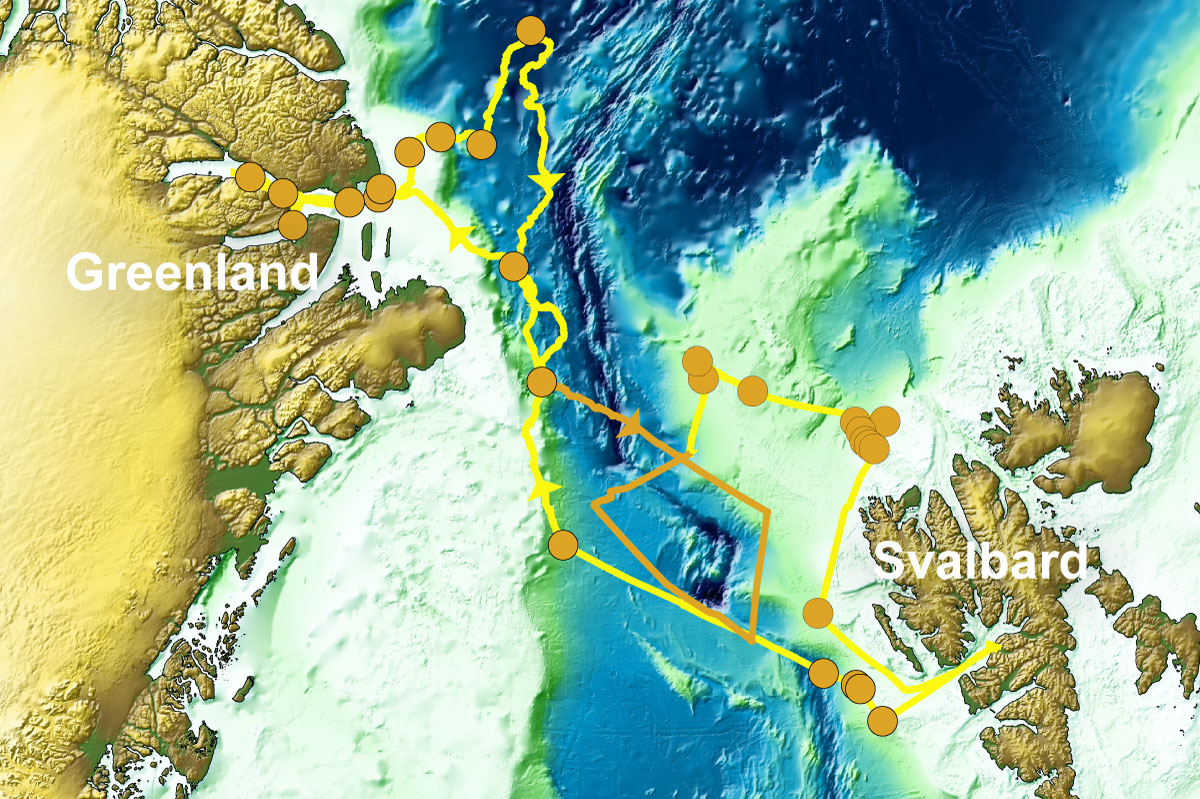

A highlight of the trip was the exploration of the rarely visited Independence Fjord at the northern tip of Greenland. According to the expedition’s co-lead Jan Sverre Laberg (UiT), it resembles what the Sognefjord would have looked like 10,000 years ago, towards the end of the last ice age. Independence Fjord is so little known because it is usually locked in by sea ice. The only water depth information available to the captain consisted of two soundings. Now, after FF Kronprins Haakons passage in the fjord, there are millions of depth datapoints.

Watch our video

Sediment cores had never been collected there either, and the science team collected many. At first, the soft nature of the fjord sediments meant that core tubes came back up empty, their content running out just as they were hoisted above the water line. Fortunately, two coring veterans, Dag Inge Blindheim (NORCE) and Stig Monsen (UiB), along with Kronprins Haakon’s experienced crew, devised a strategy to secure the cores. It involved using a boat hook to ensure the multicorer’s retaining plates (think of them as small doors at the end of the tubes that close automatically right after coring) were firmly shut.

Cores were gathered at four stations in the fjord system, and analysing them will help scientists learn not only about the fjord’s history, but also about the Greenland ice sheet, what it contains and what it releases in the ocean as it melts due to global warming.

“It’s very exciting to do science in such an untouched area, says expedition co-lead Bjørg Risebrobakken. Everywhere we look, we can learn something new. We felt a great responsibility to get it right and gather as much data as possible.”

Unravelling the Arctic Ocean’s past

The Arctic Ocean will be ice free by the end of the current century. The only way we can prepare for this is by learning what the conditions were in the distant past, before human influence. There have been periods in the past when the Arctic Ocean was ice-free, and we can learn about the conditions during those times by examining what scientists call the sediment archive.

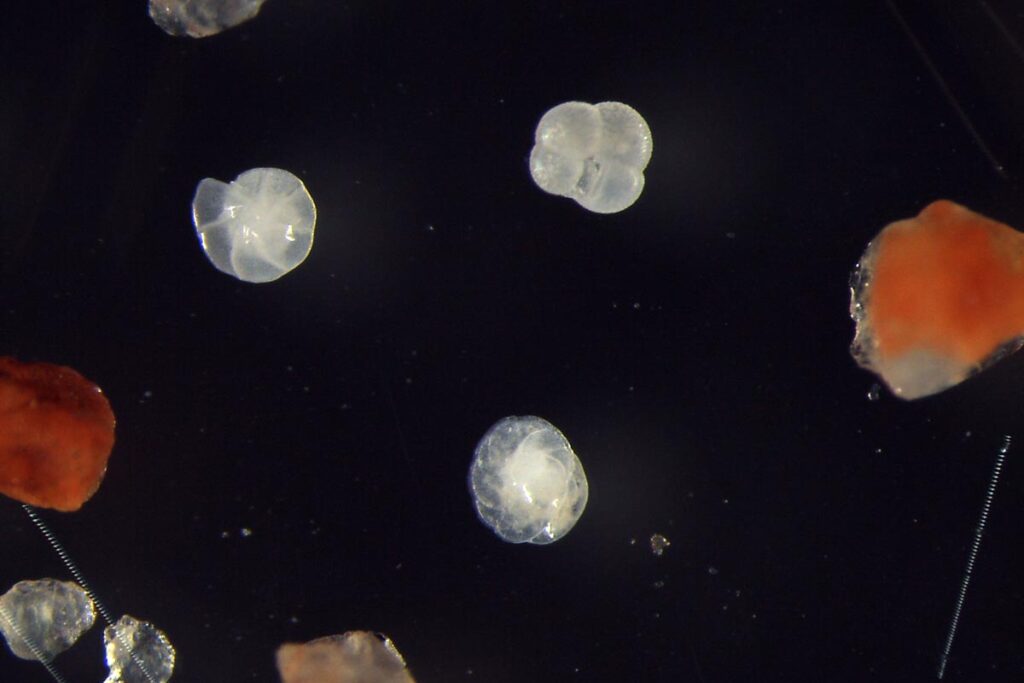

Sediments, as they get deposited at the bottom of the ocean, are shaped by the conditions they exist in. Since they are deposited more or less continuously, you can look into the past by looking at the sediments. The deeper you go, the farther in the past you’ve come. Scientists can deduce what the ocean conditions were in the distant past by looking at clues in the sediments; for example, the remnants of small organisms called forams and the chemical composition of their microscopic shells.

Understanding the area’s deep history

The Arctic Ocean was not always as well-connected to the Atlantic as it is today. The opening of the Fram Strait started about 24 million years ago, and it took a few million years for the first deep-water exchange to occur between the two oceans.

We know this because geologists and geophysicists have looked at the area very closely, and created models to recreate what happened. “When we gather more data, we can improve these models a little bit, says Alexander Minakov (UiO). The past is the past, so we can’t perform direct experiments, but we can use our data to create different models, and then see which ones give results that are closest to our reality today. »

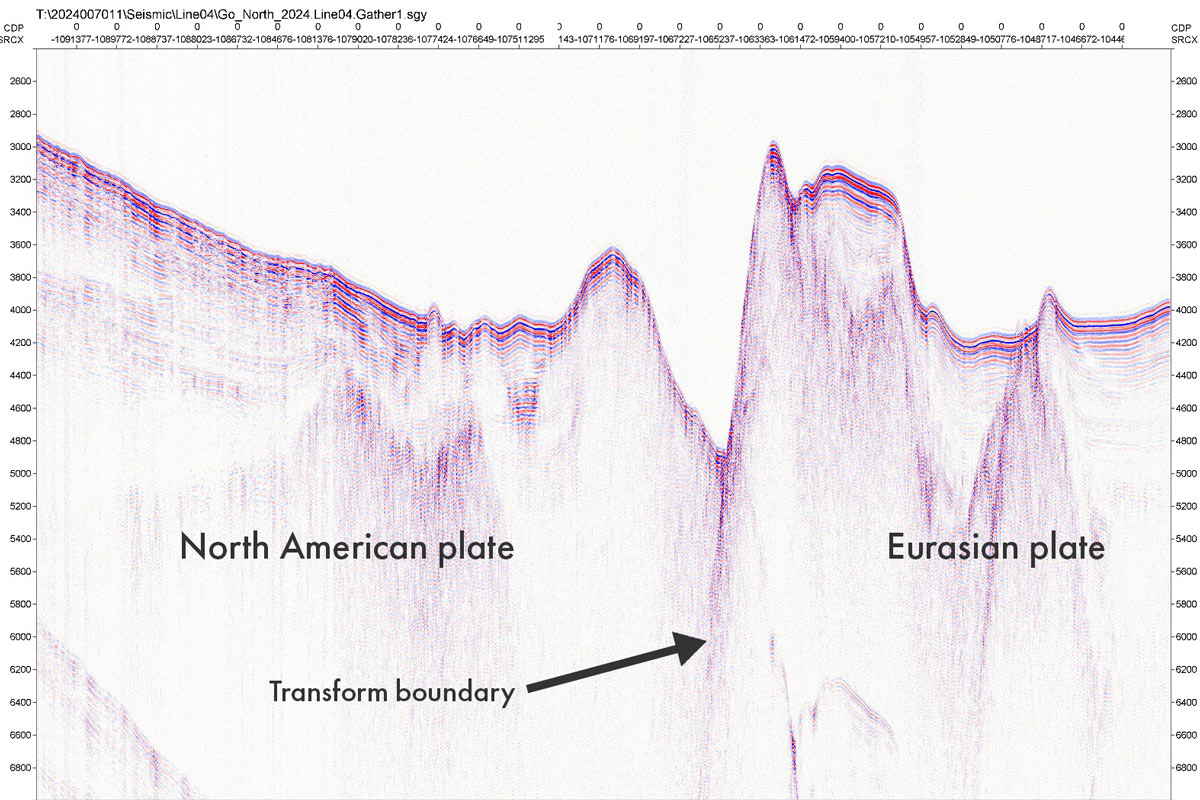

Alexander is excited about the geophysics data gathered during this expedition. To understand what he’s excited about, we need to know that at the middle of the Fram Strait lies a boundary that is very important and interesting to geoscientists. This is the boundary between the North American continental plate and the Eurasian continental plate.

When two continental plates move apart, they form what is called a mid-ocean ridge, creating new ocean floor. Sometimes, along a mid-ocean ridge, the delimitation between the two plates turns at a sharp angle, and suddenly the plates are not moving away from each other along that line, but rubbing against one another. Geoscientists refer to this as a transform boundary.

GoNorth 2024’s seismic lines, carried out by the team from GEUS (Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland) and totalling 724 kilometres, cross both of those types of boundaries.

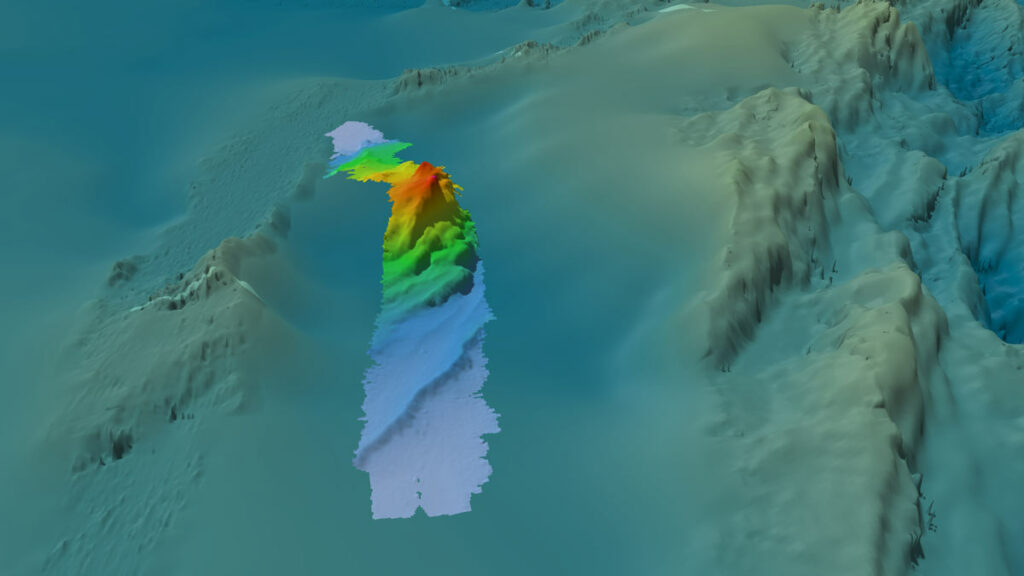

In addition to the seismic surveys, other geophysics data were collected. This includes gravimetry, which reveals hidden structures by measuring slight variations in the Earth’s gravity field. Magnetometry does the same, but by measuring variations in the magnetic field. Bathymetry, essentially mapping the ocean floor, was also carried out during the entire trip, by Nicki Riber Andreasen (GST – Danish Geodata Agency), much of it covering areas that were until now entirely unmapped. All of these measurement – gravimetry, magnetometry and bathymetry – have produced high-resolution results that will be analysed for years to come.

Expedition co-lead Jan Sverre Laberg points out the value of another key measurement performed during the trip: heat flow. “Heat flow data tells us about how heat travels from the interior of the Earth to the surface, he says. For the Arctic Ocean, this data is extremely sparse, which makes any new addition valuable.”

Pushing the frontier of seafloor microbiology

We don’t hear about them very often but microbes living in the sediment layers at the bottom of the sea play a crucial role in cycling chemical elements between the subseafloor and the ocean. Before this expedition, our knowledge of life in the deep subsurface sediments found in the central Arctic Ocean was based on just 3 samples with a combined volume of a few cubic centimetres. Now, thanks to the work of the science team, scientists at UiB will be able to paint a clearer picture of the Arctic Ocean’s subseafloor microbiology.

GoNorth 2024 in numbers

- 3850 kilometres sailed

- 122 short sediment cores gathered with the expedition’s two multicorers

- 32 longer gravity cores

- 32 analyses of the water column with CTDs

- 4 seismic survey lines totalling 724 kilometers and including magnetometry

- Continuous bathymetry, sub-bottom profiling and gravimetry

- 4 heat flow measurements

- 4 plankton net samplings from the Independence Fjord system

- 6 polar bear sightings

Shaping the next generation of experts

A key objective of GoNorth is to help educate the next generation of Arctic Ocean experts. On this expedition included no fewer than five PhD candidates, in fields such geology, geomicrobiology, cybernetics and computer vision.

Smooth sailing for GoNorth’s 3rd expedition

One way in which this expedition can be described as an unmitigated success is by the sheer volume of data and samples collected. The expedition’s only sour note was at the very start, when it was discovered that a shipping mix-up meant that an important piece of equipment would not be available during the trip. The University of Bergen’s Calypso-corer, an instrument using a piston to take sediment cores of 15 to 20 metres, was stuck in a warehouse in Tromsø. Other material had also gone missing, but unlike the Calypso, it was small enough to be shipped by plane, causing only a few hours of delay.

After those initial hiccups, the expedition was blessed with favourable conditions, both ice and weather, resulting in more data being collected than anticipated. Winds of upwards of 23 m/s caused rough seas which would have put a stop to any coring activities, but they coincided with the seismic part of the programme, so they caused no interruption or even slowdown of activities.

The Morris Jesup Rise was not visited, due to heavy ice in the area, and to the fact that the crew aboard Swedish icebreaker Oden had to abandon their plans of meeting with Kronprins Haakon. The ice between them and Morris Jesup Rise was just too thick to make the trip worth the time, and they elected instead to turn around and go back via the west side of Greenland.

About GoNorth

GoNorth’s objective is to push the boundaries of knowledge about Norway’s neighbourhood in the Arctic Ocean, from the sea floor and subsea geology, to the sea ice, via the water column. The project was launched in the wake of the 2009 decision by the UN’s Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to grant Norways territorial claims on its northernmost shelf. GoNorth was led by SINTEF from 2014 to 2023. It is now led by NORCE.

GoNorth’s third expedition started on 29 August in Longyearbyen, and returned on 19 September.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!