What is a feeder loop service

Ships grow larger, but ports do not. What happens to the small terminals that cannot accommodate these ships, or when the volume is too low for there to be economy in visiting these small ports? Naturally, this cargo ends up on the roads, either travelling to the nearest large port, or going hundreds of kilometers across boarders straight to the customers. This puts pressure on the roads and hence investments in road maintenance and expansion is necessary.

Several research projects and commercial initiatives have investigated “feeder loops”. A feeder loop combines the economy of scale that benefits large ships with the flexibility and outreach of small highly automated ships. These are commonly referred to as mother and daughter ships.

These mother and daughter ships work together to avoid the necessity for these large mother ships to travel unnecessary distances for small amounts of cargo. So they drop it at a coastal transhipment terminal, where it is picked up by the daughter ship who distributes closer to customers.

What is the potential of feeder loop services?

SINTEF Ocean conducted a study in the Horizon 2020 project AEGIS, together with North Sea Container Line (NCL) and Trondheim Havn IKS. Here we explored a new feeder loop service in Trondheimsfjorden in Norway, where the waterborne cargo transport is limited today. The feeder loop is enabled by a new transshipment terminal in Hitra Kysthavn, operated by Trondheim IKS. NCL and other short sea shipping operators can use this to limit the port calls for their bigger short sea vessels.

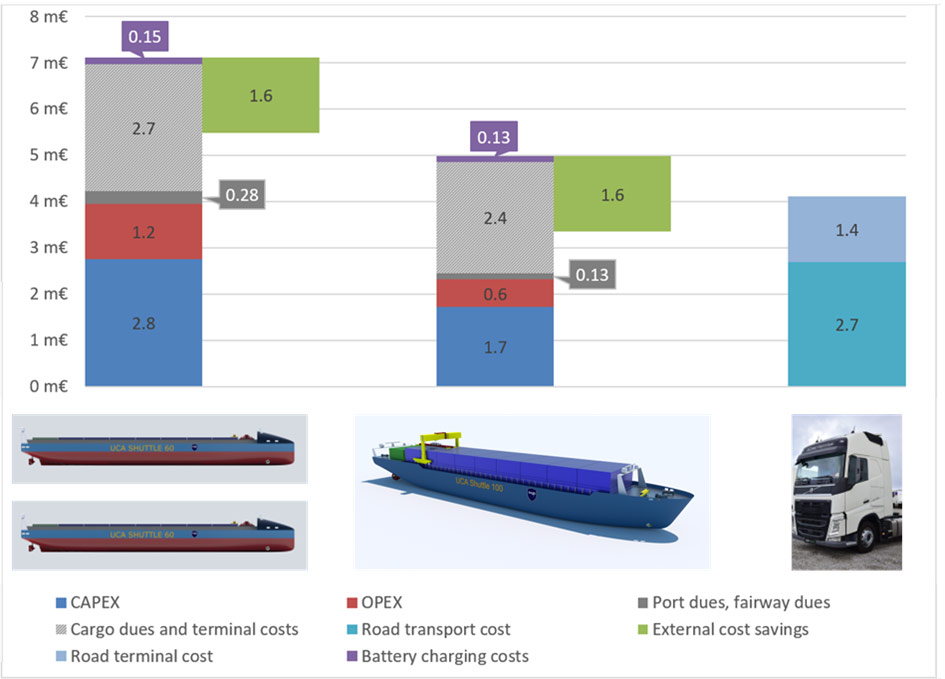

This means that these vessels can either have a shorter turnaround time to the continent or take on more containers when combining these with daughter ships in several regions of the Norwegian coastline. The study was based on two types of highly automated ships with battery-driven propulsion system. The capacity of the ships were 100 20-foot containers for the biggest alternative and half the size of Yara Birkeland, which means 60 20-foot containers for the smallest.

Cost competitive and societal benfits

The results of the study showed that these types of feeder loop services deployed in the Trondheimsfjord region can be cost competitive to truck transport. Additionally, using these types of green feeder loops to get closer to the customer has a range of societal benefits. EU recognizes this importance in its policies and research programmes.

The ships are green and small, which means they do not currently have to report to the EU ETS system, and the roll-out of ETS2 for truck fuel may give a further competitive advantage in the near future. Unlike trucks who transports their cargo on roads, these vessels do not need additional infrastructure to sail their voyages in the fjord leading to significant reduction of external costs. By including the monetised external costs, the feeder loop service would even come out economically positive when compared with trucks for the same transport work. Policy is not yet in place for the taxation of wider external costs (excluding GHG).

External costs – what is it and why does it matter?

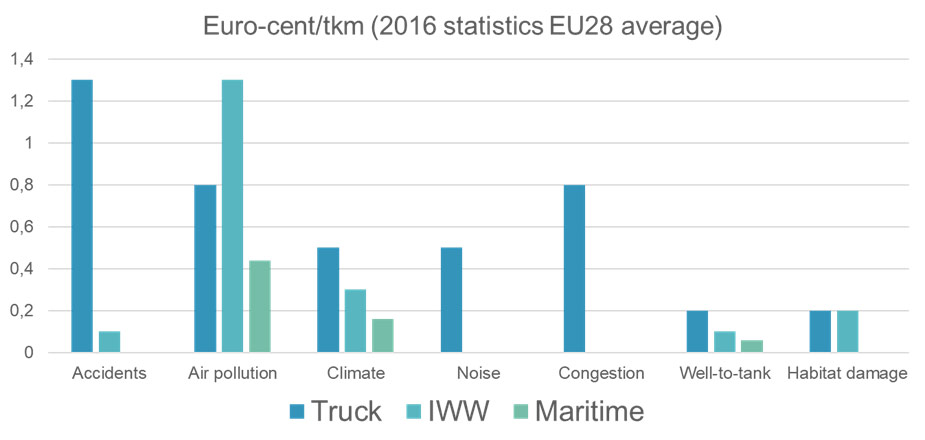

External costs related to transport is rarely a topic in media. External costs are defined as costs incurred by a third party as a result of a transaction which the third party is not part of. Societal costs from transport are such costs, and includes accidents, pollution, road congestion, climate and habitat damage.

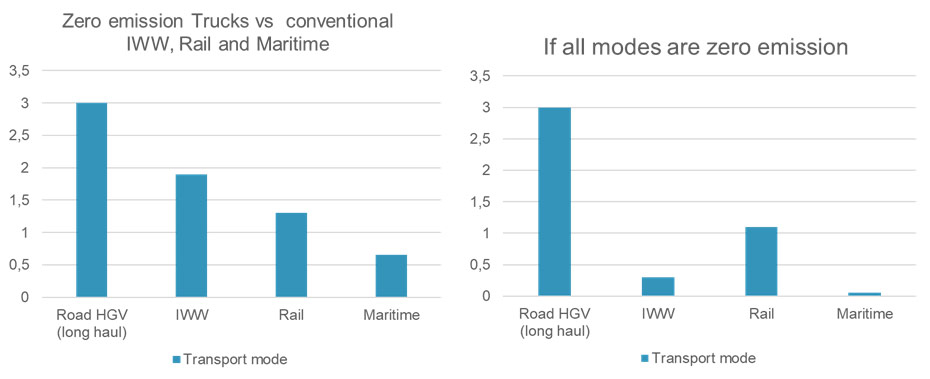

When looking at zero emission vehicles and vessels for all transport modes, there is no difference in external costs for roads, but large differences for the other transport modes, and most notably for inland waterways and maritime. As such, making trucks electric will not solve the challenges related to these external costs.

The electric trucks are heavier than conventional gas- powered trucks, but is still regulated to the same gross vehicle mass (GVM) as previous. This has direct consequences on the cargo volume that is transferred per journey, increasing the end consumers cost per unit. Alternatively, policy is put in place to have an increased GVM for these electric trucks, which will then be an incurred external cost for society particularly due to the even higher road degradation rates caused by this weight.

While GHG is taxed through MRV, other external costs are not. They continue to have a direct impact on people’s everyday lives, policy and the environment.

Further research and developments of maritime feeder loops

The municipality of Bergen plans to move the city centre terminal of the Port of Bergen to Ågotnes. 11 nautical miles by ship, or 27km by truck outside of its current location in central Bergen. Moving the city centre terminal entails a need for cargo transport between Ågotnes and Bergen. That puts a lot of pressure on the local roads that are narrow and goes through small villages and where the speed limit is low. If the cargo is to travel from this new terminal via road, the road infrastructure needs significant upgrading.

SINTEF Ocean works together with Port of Bergen, Kongsberg Maritime and ASKO Maritime in the Horizon Europe project SEAMLESS, to do a feeder loop study on this case as an alternative. The hypothesis is that a feeder loop service will solve this issue. From a societal perspective you will eliminate the need for expanding the road infrastructure, with the added benefit of providing a green, environmentally friendly alternative, since these daughter ships are planned to be electric. ASKO Maritime has already shown that such a shuttle service works for Moss – Horten, and they now see the potential also in the Bergen area as well as Northern Norway.

If you are curious about further developments within maritime feeder loops, follow the SEAMLESS project on LinkedIn and do not hesitate to reach out to our researchers at SINTEF.

Comments

Great article the breakdown of how feeder loop services can ease road congestion and boost sustainable transport is inspiring. Looking forward to seeing these green maritime innovations roll out and reshape the future of shipping!

Thank you! We are continuing this work in the HEU projects SEAMLESS and AUTOFLEX. Feel free to get in touch if you want more details or see potential for collaboration.