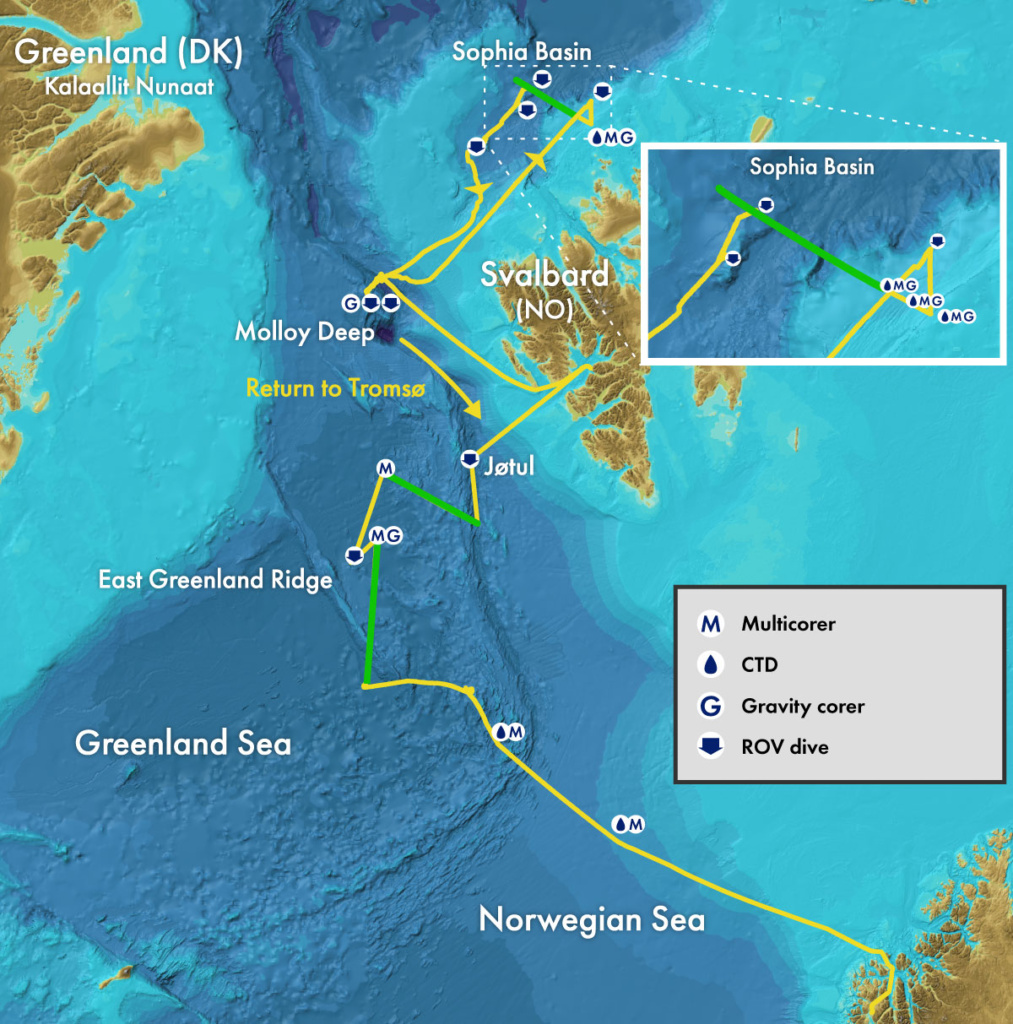

The stormiest of the four GoNorth expeditions has drawn to a successful close, returning to port in Tromsø on the evening of 16 December. Although the primary target (Ultima Thule) could not be reached due to an engine issue, the science team yielded a wealth of scientific data not by following a fixed script, but by adapting continuously to the Arctic conditions that shaped every decision along the way.

Where the maps fade out

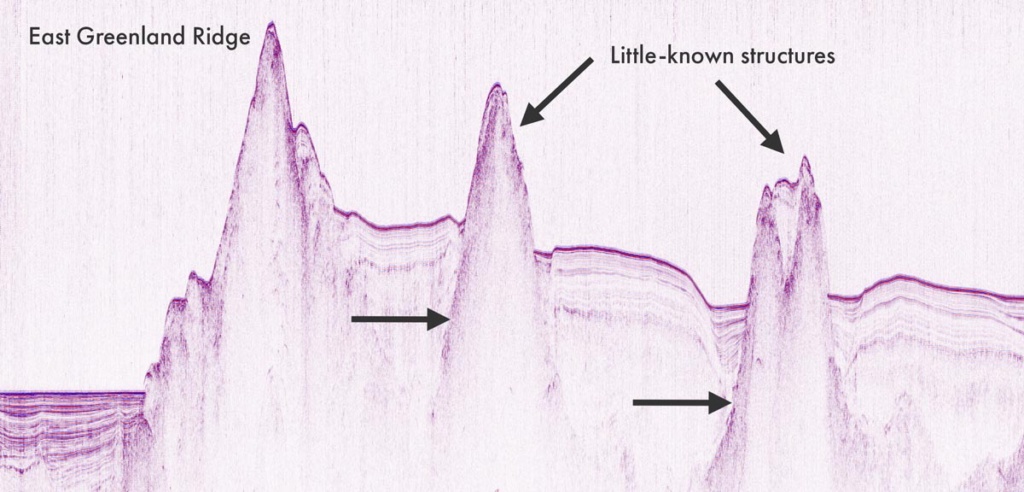

A highlight of the trip was how it shed light on seafloor structures that have so far remained poorly understood. A seismic line across the East Greenland Ridge and two adjoining features will help reconstruct the area’s deep geological history, imaging both the seafloor and what lies beneath.

What made this expedition distinctive was that seismic profiling was only one part of a broader, integrated approach. As the ship moved through the area, bathymetry was collected continuously, gradually revealing the shape of ridges, basins, and seamounts on the seafloor. At the same time, continuous measurements of the Earth’s gravity and magnetic fields recorded subtle variations linked to the rocks below, offering clues about their composition and structure.

In addition to remote sensing, the expedition also explored selected locations along the seismic lines with a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). These dives made it possible to observe the seafloor directly and to collect rock samples, that provide hard evidence — quite literally — of what the seafloor is made of. Much of the analysis work begins only once the expedition is over, as the bathymetric, seismic, gravity, and magnetic datasets will be processed and analysed in detail.

The same strategy, combining remote sensing and ROV rock sampling, was used at both the East Greenland Ridge and the Polarstern, a seamound in the Sophia Basin (north of Svalbard) about which very little is known.

Sediment sampling: Reading the seafloor’s memory

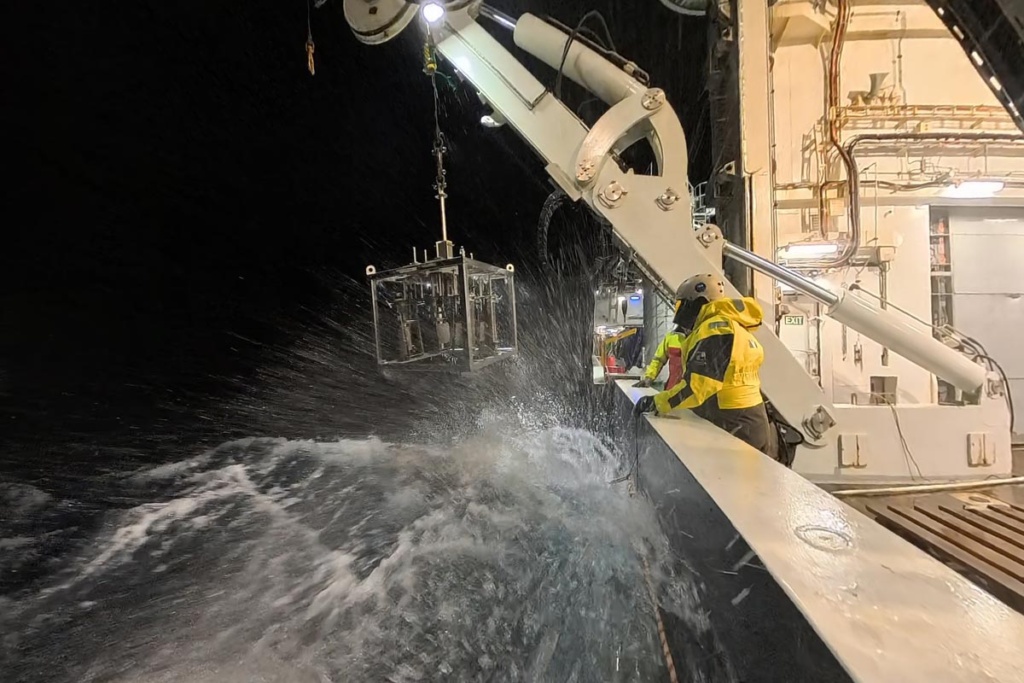

Another key activity of this expedition was to gather sediment samples. At depths of up to 4000 metres and in sometimes choppy seas, this is anything but straightforward. Nevertheless, the coring on this trip has been remarkably successful, with nearly every sampling attempt returning full cores.

Because ocean floor sediments act as an archive of sorts, gathering them and analysing them is useful for a wide range of purposes. Some samples will be sent to SINTEF to be analysed for contaminants. Others, taken along the slope of the Sophia Basin, north of Svalbard, will be used for paleoceanographic studies. By analysing grain size variations in these sediment cores, researchers can reconstruct how ocean currents in the area have changed over time, with a particular focus on linking the strength of Atlantic water inflow to past episodes of abrupt climate change.

eDNA to map biodiversity

One important use of these sediments is to study biodiversity through environmental DNA, or eDNA. By analysing genetic traces preserved in the sediment, researchers can identify which organisms live — or have lived — in an area, from large animals to microscopic life, even when they are never observed directly. Under the lead of Thomas Dahlgren (NORCE) samples were taken from several distinct deep-sea regions to compare the fauna they contain. This work will help clarify how different these ecosystems are, knowledge that is increasingly relevant as discussions around deep-sea mining intensify.

Pore fluid to understand the microbes of the deep

Another way sediments can be read is through pore fluid: the water trapped in tiny spaces between sediment grains. Using a syringe fitted with a special filter, scientists carefully extract this fluid from split sediment cores and analyse its chemical composition at different depths. These chemical profiles reveal which substances are available as energy sources, offering insight into what kinds of microbes live in the sediments and how active they are deep below the seafloor.

A focus on biology

This expedition brought together the largest group of biologists of any GoNorth expedition to date. The ROV was used extensively to explore how life is organised on the deep Arctic seafloor. Near the Jøtul hydrothermal vent field, UNIS scientists Carla Lopez Mateo and Arunima Sen used the ROV to take pictures that will later be put together to create a mosaic of a section of seafloor. The idea is to document which species are present, how they are distributed, and how they relate to the underlying geology. They also used the ROV to collect sediment cores to look at meiofauna: tiny animals that live between grains of sand at the bottom of the sea.

Anthropology at Sea

Among the geophysicists, biologists, and crew on board was one researcher whose focus was not the seafloor, but the people studying it. Anthropologist Marta Gentilucci (UiB) is using the expedition as part of a Marie Skłodowska-Curie project on deep-sea mining, examining how knowledge, expectations, and uncertainties take shape around an industry that has yet to begin. By living and working alongside the scientists at sea, she gains close insight into the practical challenges, expertise, and relationships that would also underpin any future attempt to extract resources from the deep ocean.

A custom-built sensor module to map sea ice

Although RV Kronprins Haakon did not enter the thickest ice during this expedition due to engine issues, it still operated in sea-ice conditions that allowed PhD candidate Ashiqul Alam Khan (NTNU) to test his custom-built sensor platform. The system combines stereo cameras, a thermal camera, and the ship’s own navigation and environmental sensors into a single, synchronised measurement chain; when ice floes are overturned by the ship, their exposed undersides make it possible to estimate ice thickness directly using three-dimensional reconstructions. Each thickness estimate is linked to precise position, time, ship motion, and weather data, creating a dataset that can later be used to explore how ice thickness and floe properties vary under different environmental conditions and to improve future sea-ice maps.

Tracing moisture pathways with water isotopes

Throughout the expedition, an instrument measuring isotopes in atmospheric water vapour ran continuously on board FF Kronprins Haakon, providing near–real-time data thanks to daily calibrations and satellite connectivity. These measurements reveal where the moisture came from and how it moved through the atmosphere, helping scientists understand evaporation and moisture transport over ocean, ice, and open water. As a core component of the upcoming Arctic Ocean 2050 project, the GoNorth expedition served as a full-scale test of both the instrumentation and data-processing chain, delivering a high-quality dataset that will now be used to evaluate and improve isotope-enabled climate models for the Arctic.

GoNorth 2025 in numbers

- 4548 kilometres sailed

- 31 short sediment cores gathered with the multicorer

- 4 longer gravity cores

- 17 short sediment pushcores gathered with the ROV

- 3 seismic survey lines totalling 410 kilometers and including magnetometry

- Continuous bathymetry, sub-bottom profiling and gravimetry

- 9 ROV dives

Weather as a constant companion

According to captain Karl Robert Røttingen, this was the roughest expedition ever undertaken by RV Kronprins Haakon. The ship sailed straight into bad weather at the very start of the voyage, sampling sediments while pushing north until the seas grew so rough that operations had to be halted altogether. Rough seas were encountered again on the return from the Sophia Basin, and after work at the Molloy Deep, a large weather system ultimately forced a premature turn south and dominated the long passage back to Tromsø. It is a voyage that everyone on board will remember, with sleepless nights punctuated by sudden jolts and cannon-shot bangs as waves struck the hull.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!