Tiny bubbles might not seem important, but a new study shows they can significantly affect how pressurised liquids behave. Especially when the pressure drops. For CO₂ transport systems, this means rethinking how we predict flow and phase changes during leaks or valve operations.

Transporting CO₂

An integral part of CO2 capture and storage is to transport the CO2 from the capture site to the storage site. As CO2 is a gas at atmospheric pressure, it is not very dense. To improve transport efficiency, CO₂ is pressurised and moved as a liquid, or dense phase.

If the CO2 transport system has a leak, or a valve is opened, the CO2 will want to change phase back to a gas. This is a type of boiling. But because it is caused by a pressure loss instead of heating, it is called “flash” boiling or flashing. The boiling changes how the CO2 flows. So, if we want to predict what happens during a leak or when we open a valve, we need to know when that boiling starts.

Just like water can become colder than 0°C before it freezes, a liquid can also reach a lower pressure than its boiling point before it flashes. And just like it’s hard for water to create ice crystals to freeze, it’s also hard for a liquid to create bubbles to boil. When the CO2 wants to boil, but hasn’t boiled yet, it is metastable.

So, the question is: how metastable can liquid CO2 become? When do bubbles start affecting the flow?

A new model

There are established models for predicting how bubbles form in a metastable liquid.

One of these is called classical nucleation theory (CNT). Predictions from this model fit experimental data well for a sudden depressurization at warm temperatures, but not for colder ones. This is the case for many fluids, not just CO2.

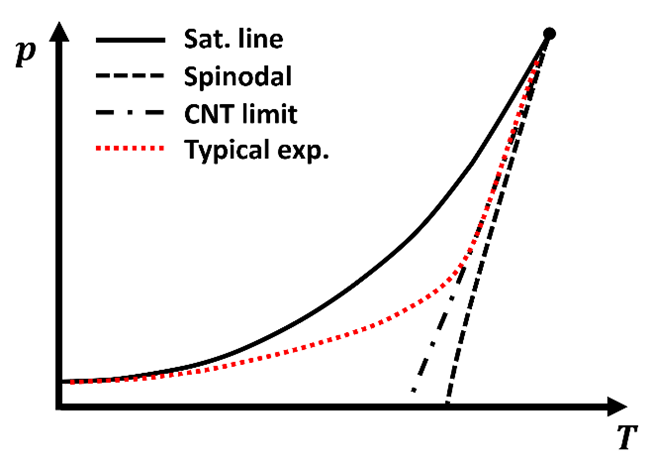

An example of the typical experimental trend is shown in the figure below.

Figure 1. Phase diagram of CO₂ with pressure (p) and temperature (T). The Sat. line (solid black) marks the boundary between the liquid and gas phases. CO₂ is in the liquid phase above this line. Below it, CO₂ is usually a gas. But can remain as a metastable liquid until it reaches the Spinodal line where the liquid becomes unstable. The CNT limit (dash-dot line) shows the theoretical boundary from classical nucleation theory. And the Typical exp. curve (dotted red) represents typical experimental observations.

During work in the IntoCloud and COREU projects, we have developed a new model which can explain what happens at colder temperatures. The idea is based on tiny bubbles that are already trapped on the surface where the flow is passing through.

The presence of such bubbles is well known and helps explain how water boils when heated in a pot.

Tiny gas pockets get trapped at imperfections on the pot’s surface. Water evaporates into them, forming larger bubbles that are released and rise to the surface. This is why you often see bubbles forming and rising from specific spots when water boils. Those are the places where the tiny bubbles were stuck.

When we account for tiny bubbles stuck on the surface where the liquid flows in our new model, we can fit the experimental data for both CO2 and water depressurisation.

These tiny bubbles also explain why liquids don’t become metastable if the pressure is reduced slowly. The liquid then has time to evaporate into the bubbles, and the flow remains in equilibrium.

Relevant for fields using pressurised liquids

When we account for tiny bubbles stuck on surfaces, we can predict how liquid CO2 will change phase back to a gas as it is depressurised.

Since the liquid phase is much denser than the gas, the CO2 flows in a very different way if it is in one phase or the other. Understanding this phase change will help in predicting mass flow of CO2 through valves, and the pressure on a potential crack or fracture in transport equipment.

Though this work was done with the application of CO2 transport, the results are general and relevant for many other fields using pressurised liquids. From space shuttle launchers to nuclear cooling systems – the flow will be affected by tiny bubbles.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!