We need well-crafted plans to achieve ambitious climate goals. That’s why EU member states have recently updated their National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) for the 2021–2030 period. These plans are meant to coordinate efforts toward a net‑zero society, ensure energy security, and enable sustainable economic growth. Insights from the plans can serve as a foundation for realistic model simulations of how the European energy system might develop in the lead-up to 2050. However, the plans are long and bureaucratic, making it a time‑consuming ordeal to manually sift out the relevant information.

Author Simon Wego is a summer scientist at SINTEF Energy Research, for the summer of 2025. Interested in joining next year? Keep an eye out for the 2026 Energy Summer Jobs positions (link in Norwegian). Positions will be announced in October.

During my time as a summer scientist at SINTEF Energy Research, I developed an AI‑powered program that can automatically extract information from NECPs relevant to the GENeSYS‑MOD energy system model. The system is designed to identify which parts of the text contain relevant parameters, such as planned emission reductions or investments in renewable energy, and retrieve this information in a clear, structured format. The foundation of the application is the Python library Haystack, which provides access to state-of-the-art natural language processing technologies in a powerful and intuitive framework.

The technology applied with the Haystack framework is called Retrieval‑Augmented Generation (RAG). In short, it works by splitting the document into manageable sections, retrieving the ones relevant to a given query, and then letting a large language model summarise the content of those sections. The advantage of using this kind of pipeline, rather than relying solely on a large language model (like OpenAI’s 4o model), is that you can better control exactly where in the text the information comes from. It also makes it easier to meet requirements for scalability and reproducibility.

But how can this system “understand” which parts of the document are relevant to the query?

This is where an important aspect of modern language processing comes into play—embeddings. A text embedding is essentially a translation of natural language into a numerical vector representation that language models can work with more easily.

Unlike traditional translations of language into numerical form, which often just map words to numbers one‑to‑one, embeddings have the advantage of encoding semantics directly into the vectors. In other words, these vectors carry information about what the words they represent mean, based on their relationship to other vectors.

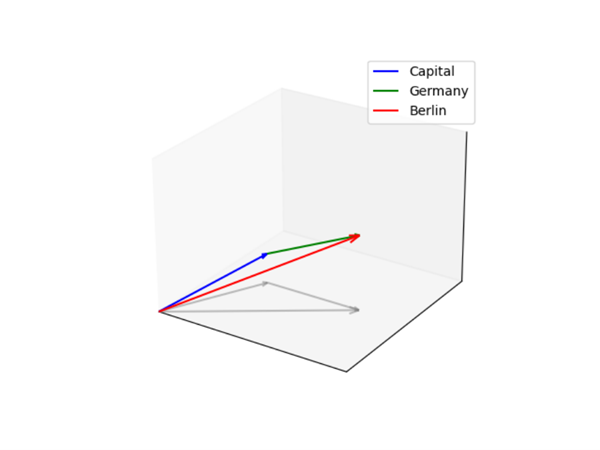

Let’s look at an example to make this clearer. Suppose we take the words Germany and Berlin and convert each into its own vector representation using an embedding model. If we then compare the vectors for Germany and Berlin, we’ll find that they point in roughly the same direction in vector space, because both are related to something German. Furthermore, if we take the Berlin vector and subtract the Germany vector, the resulting vector will most likely end up very close to the vector representation of the word capital.

Much of the strength of modern language models comes from this kind of semantic language encoding. It’s through these translations into vector representations that language models can, in a sense, “understand” meaning and relationships within natural text.

Semantic search in RAG

Now we can look at the complete workflow of the RAG pipeline. It all starts with preprocessing an NECP PDF. This means the original PDF file is converted into Haystack’s built-in document format and cleaned of any unnecessary characters. The document is then split into paragraphs of the desired length.

After preprocessing, the content of each paragraph is translated into a set of embeddings using an embedding model. To capture the essence of each paragraph, all embeddings in that paragraph are aggregated into a single embedding vector, which is essentially an average representation of the entire paragraph.

To search for information in the text, you can then formulate a question that targets the information you want to find and translate that question using the same embedding model used on the text. A semantic search works by finding the paragraphs with text embeddings closest to the embedding of the question. Since we’re operating in a vector space, we can easily calculate the “distance” between the embedding vectors.

A distance score close to 1 means the vectors point in the same direction, indicating that the question and the paragraph are semantically similar, making it likely that the paragraph contains information relevant to the query.

The strength of semantic search lies in the fact that it’s the essence of the text that determines whether you get a match. This method captures the meaning of a paragraph across different phrasings in the document, so you’re not dependent on finding the exact right keywords to get the result you’re after.

Semantic search is also preferable when you’re looking for information that’s conveyed in an indirect way in the text. However, if you know exactly how the information you’re after is phrased in the document, keyword search can be just as useful. Another advantage of the latter is that it’s less sensitive to how you formulate your query compared to semantic search.

Put another way: with keyword search, the paragraphs that literally contain the key terms from your query will be retrieved, while with semantic search, the paragraphs retrieved are those that most closely match the meaning of your query, according to the embedding model.

So, how do we take advantage of both methods?

Hybrid approach to information retrieval

One of the great things about RAG pipelines from Haystack is that you can easily implement hybrid search and get the best of both worlds.

In hybrid search, text paragraphs are evaluated for their relevance to the query using both semantic search and keyword search. For keyword search, a well‑known algorithm called BM25 is often used, which assigns higher relevance scores to paragraphs containing the same keywords as the query.

In the RAG pipeline, relevant paragraphs are retrieved from the text using both the BM25 algorithm and semantic search. Once these independent processes have found the paragraphs they each consider most relevant to the query, the combined set is passed into another component called a Reranker (sometimes called Ranker).

Both semantic search via embeddings and the BM25 algorithm are designed to be efficient and retrieve relevant information quickly. The downside is that this can come at the expense of accuracy. That’s where the Reranker comes in, acting as a kind of filter that re‑evaluates the relevance of the retrieved paragraphs.

The Reranker is a separate language model known as a cross‑encoder, trained to process the paragraph and the query together in a single input to assess relevance. This is different from the embedding model, which can be called a bi‑encoder because it processes the paragraph and the query separately. The Reranker then returns what it considers to be the most relevant paragraphs, along with their relevance scores (ranging from 0 to 1).

Once you have a result from the Reranker, you’ve completed the retrieval stage of the RAG pipeline. In the application I’ve been working on, these results are stored as retriever logs, which include the query, the retrieved paragraphs, and metadata such as the page number the paragraph came from and its relevance score.

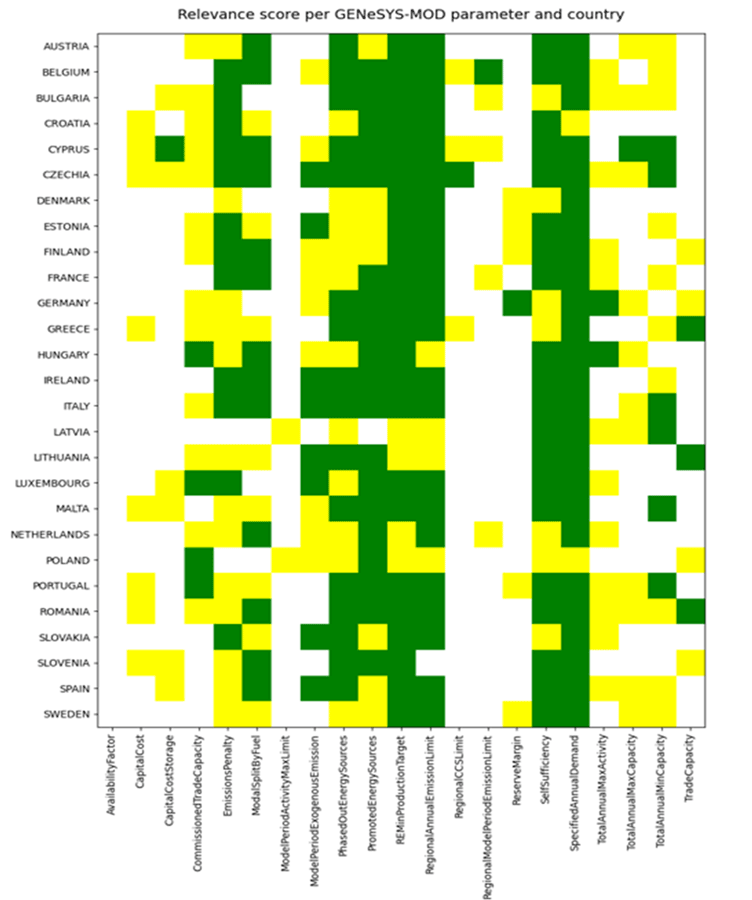

As mentioned, the retriever stage of the system runs fairly quickly, making it easy to get an overview of which countries’ NECPs contain paragraphs relevant to different GENeSYS‑MOD parameters. The figure below shows a relevance score matrix, where green cells indicate findings with a relevance score above 0.8 for the given parameter in that country’s NECP. Yellow cells represent scores between 0.5 and 0.8, while white cells indicate scores below 0.5.

As we can see from the figure, most EU countries mention something in their NECPs that is relevant to the SpecifiedAnnualDemand and SelfSufficiency parameters, dealing with projected energy demand and self‑sufficiency, respectively, but very few NECPs contain anything relevant to the RegionalCCSLimit parameter, which concerns greenhouse gas storage capacity.

“Challenges related to precision and accuracy will always arise when working with AI.”

With an overview like this, you can dive into the retriever logs and read the paragraphs with the highest relevance scores to see if they contain any figures or insights you can use in the energy system model.

It’s worth noting that even if a paragraph receives a high relevance score from the reranker, that doesn’t necessarily mean it answers the query in a satisfactory way. For example, the paragraph’s language might closely resemble the wording of the query without actually mentioning any specific figures.

On the other hand, there’s no guarantee that some paragraphs deemed irrelevant don’t actually contain relevant information. Challenges related to precision and accuracy will always occur to some extent when working with AI. However, the performance of RAG applications like this can be improved by fine‑tuning the language models with datasets that provide more domain‑specific examples of what should be considered relevant or irrelevant for a given query.

One of the nice things about using Haystack in this context is that the RAG pipeline has delivered satisfactory results without the need to fine‑tune any of the available models for the project.

Generative summarisation of relevant paragraphs

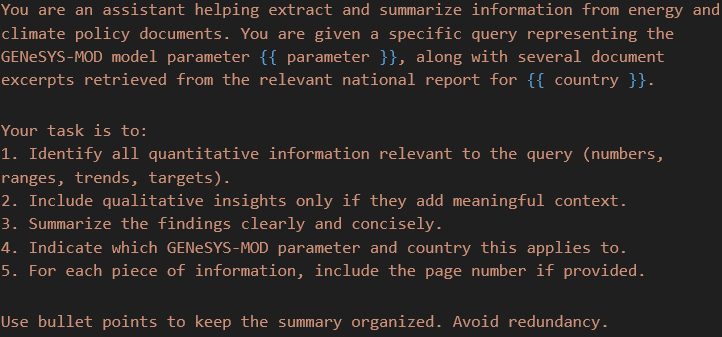

We can further reduce the amount of text we need to read to extract information by using a language model to summarise the relevant paragraphs for us. This final step is the generator stage of the RAG pipeline, where you can integrate GPTs (Generative Pretrained Transformers) from, for example, OpenAI directly into the Haystack framework.

In the application I worked on this summer, I used a SINTEF‑owned Azure resource to access an API key, which allowed me to use OpenAI’s o4‑mini model as the generator. This generator works just like a chat model in that you give it a detailed prompt describing what it should do and how it should use the relevant paragraphs it receives from the retriever log. The figure below shows an example of such a prompt.

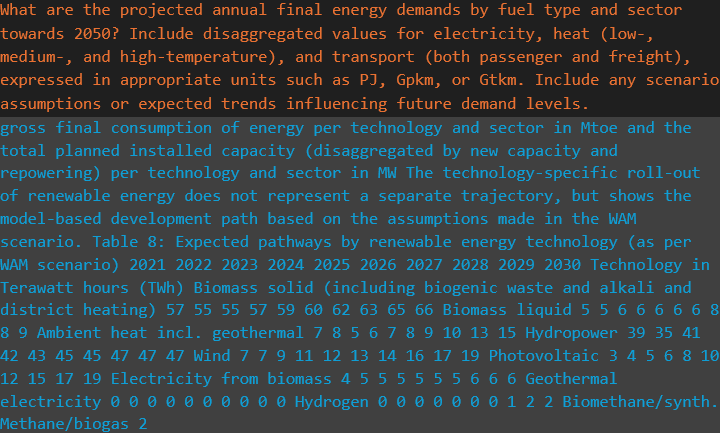

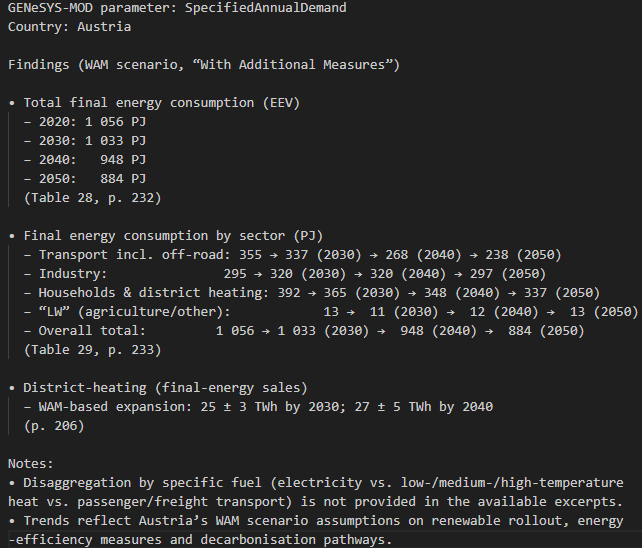

For each GENeSYS‑MOD parameter and each country, the generator’s answer is stored in a text file. Figure 5 shows the generator summary for SpecifiedAnnualDemand and Austria. In this way, relevant information from NECPs is collected and summarised by the RAG pipeline, and hopefully, the results of this project will help save time in the search for relevant energy and climate data, while contributing to more realistic simulations of the European energy system.

Working on this project has given me the chance to take a deep dive into AI‑driven methods for information search and retrieval. I have learned a lot, and I have been particularly fascinated by the usefulness and elegance of text embeddings. The AI research field is in quite a developmental rush, but I think RAG-like systems could stand the test of time and be very useful in many other scenarios where you need to quickly search through unstructured (non‑tabular) text documents.

For my own part, it’s quite likely that I will use a similar system as a tool for literature review when I start my master’s thesis next spring. If exploring similar information‑retrieval systems sounds interesting, I can highly recommend checking out Haystack.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!