With wind farm developments rapidly growing around the world, a lot of attention is dedicated to understanding and mitigating their possible negative impact on birdlife. Impacts might range from habitat loss to fatalities due to collisions with wind turbines. These can be reduced by avoiding predicted high-risk areas during the planning phase of new wind farms, followed by the application of mitigation measures during their operation. In this article, we introduce a new concept that prevents bird collisions with rotating blades of wind turbines using control engineering.

The basic idea was formulated already in 2015, but is now receiving strong interest from the wind industry. Sustainable wind development is an important activity in our NorthWind Research Centre, and we seek to further mature the technology so that it can be put into practical use in wind farms, offshore and on land.

Why do birds collide with rotating blades of wind turbines?

Before proposing any new solutions for preventing collisions, it is important to understand why some bird species collide with wind turbine blades. One reason can simply be that they do not perceive the rotating blades a few meters ahead of them. Therefore, they do not recognise them as objects that should be avoided.

As the bird is approaching the wind turbine, the image of rotating blades changes too quickly to be processed by their eyes and appears as a transparent blur. This is known as motion smear, a visual effect that happens with fast-moving objects. An example of such an effect can be observed when hummingbirds are flying, and their wings are nearly invisible to human eyes.

In addition, some bird species have a tendency to look laterally and downwards while flying (to search for food or mates, for example) which may be more relevant to them than looking ahead in the open airspace. When doing that, they cannot see any objects placed in their direction of flight, and become more prone to collisions.

A new patented control concept to prevent collisions

The patented concept is named SKARV, which is the Norwegian translation of the bird species cormorant and an acronym for “Slippe fugleKollisjoner med Aktiv Regulering av Vindturbiner” (in English “preventing bird collisions through active control of wind turbines”).

SKARV consists of a novel active control system that makes small adjustments to the rotor speed of wind turbines after detecting the presence of birds within a certain distance of the blades. This allows the detected bird to fly through the rotor area without being hit by the blades.

The main goal is to reduce the collisions between birds and rotating blades of wind turbines without

- Interfering in the wind farm operation, i.e. avoiding turbine shutdown and consequent loss of power production.

- Disturbing other surrounding wildlife and nearby residents, which can happen when alerting sounds or lights are activated to deter birds from approaching the blades.

How does it work?

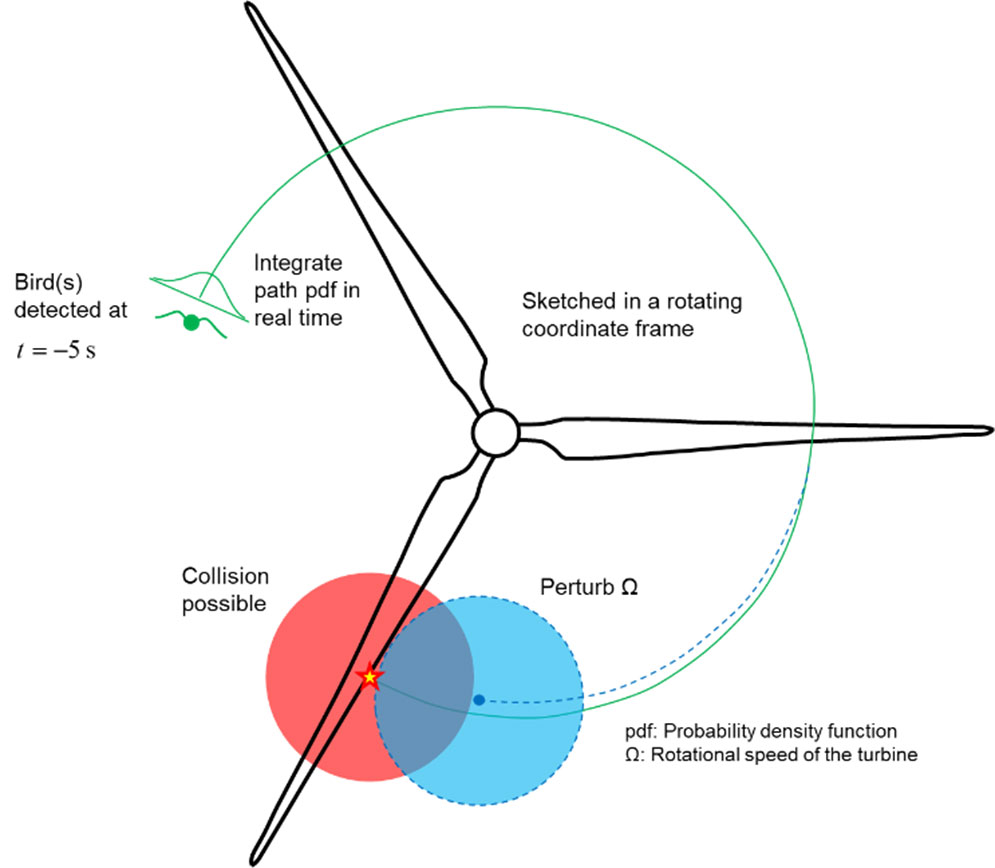

The concept is based on detecting the presence of birds with sensors, such as cameras, and performing a probabilistic estimate of their flight path. Then, the rotational speed of the wind turbine is modified by a small amount to minimise the probability of collision.

Illustration of SKARV’s concept: The colored areas indicate where the bird will be with high probability when crossing the rotor plane. A possible collision (red circle) is avoided by reducing the turbine speed and the bird crosses the rotor plane between the blades (blue circle).

Once the blades are ideally oriented with respect to the most likely flight path, there is a high probability of avoiding collision, due to the clearance between the blades and bird as it passes through the rotor. Since the speed is modified only by a small amount (either by an increase or decrease in the current speed), there is no significant loss on power production.

In case a flight path cannot be estimated with any reasonable certainty – in the case of bats or birds with highly irregular flight paths, for instance – and when a flock of birds approaches, the turbines can simply be stopped for a short period of time. In normal cases however, a slight adjustment of speed will be sufficient, preventing a collision while also avoiding loss of generation.

Wind turbines typically operate with a variable and controllable rotational speed to maximise the power extracted from wind. SKARV’s concept can be applied to a wind farm with such turbines. This will include a bird-tracking system and a dedicated software to estimate both the bird’s flight path and the desired adjustment in the rotor speed to minimise the risk of collision. The resulting speed perturbations can be introduced to the standard turbine control system.

Way forward

We have so far used computer simulations to verify that the SKARV concept can work. The simulations characterised the theoretical performance of the system, indicating that the birds should be tracked within a range of 100 m to 200 m away from the turbine, and that the concept is effective if the birds’ trajectories can be predicted at least 5 seconds in advance. The earlier this prediction, the less torque is required for adjusting the turbine rotational speed.

We now seek to further mature the technology so that it can be put into practical use in wind farms, offshore and on land. The first goal is to develop the real-time control algorithm and thereafter, we aim to conduct a field test and demonstration. If successful, the SKARV technology can be commercially available and implemented in wind farms about 5 years from now. It could potentially be done faster, depending on industry interest.

When fully developed, the SKARV technology can be implemented in both existing and new wind farms, on land and offshore. The technology will be an important measure to avoid bird collisions and make wind power more sustainable.

Comments

This is super interesting! Hope this technology gets put into practice soon as it seems to be a very promising approach to reduce production loss due to mortality mitigation and bird/bats conservation