SPOILER ALERT: This blog post contains spoilers for the film Don’t Look Up.

Unlike the dinosaurs, humans have a space programme and weapons that we can potentially use in order to avoid an asteroid-related catastrophe. The scientists in the film do everything they can to get people to take the asteroid seriously and attempt to stop it from hitting Earth.

No adults in the room

In the film, the scientists meet President Orlean (Meryl Streep), whose main concern is the midterms and the “optics”, in other words, how things will be viewed by the voters. She is also influenced by the character Peter Isherwell (Mark Rylance), the tech mogul who many people believe to be a hybrid of Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg. The newscasters in the film are focused on maintaining a good mood and most people are distracted by a celebrity break-up – not very different from in the real world.

As mentioned, everything that can go wrong, does go wrong in this film. While it is a satire, it’s still easy to get frustrated with all the ridiculous decisions the characters make and people’s unwillingness to react until they actually see the asteroid with their own eyes.

Climate vs. asteroid

Many people have noticed the link between the film’s themes and how we’re managing real-life crises, namely the climate crisis and the pandemic. Therefore, we can use Don’t Look Up to understand why climate communication doesn’t always get through to the media, general public or politicians.

However, there are two main differences between the climate crisis and an asteroid catastrophe. The first is that an asteroid is a threat that we can see (which is why President Orlean encourages her followers to “Don’t Look Up”), while greenhouse gases are invisible, and we have to look at climate change over a longer period of time to understand and realise that it’s happening. The second is that the average person cannot do anything to prevent an asteroid from hitting Earth – but they can take action (by changing their behaviour) to avoid a climate crisis.

At the same time, it’s important to recognise that if we’re to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we cannot do it alone; we have to do it together. Individual actions are important yes, but we mostly need reasoned political decisions and for industries to shift to sustainable processes.

The film’s protagonists are scientists who fight to be heard but are exposed to all possible means of suppression. You may think that climate scientists would be taken more seriously, and in real life, many people do take them seriously – we read news stories about climate research almost daily. However, aside from a small dip in the corona years, emissions are still increasing. Climate scientists have been warning us about emissions for decades, but this has not solved the problem.

The solution

So, what else can we do? It’s easy to shake our heads and deem humanity to be ridiculous and irrational. However, this is not necessarily constructive if our goal is to reach the average person and convince them to change their behaviour. There’s a lot of research on climate and research communication tactics, and in this blog, I’ve collected some examples of which ones do work and which ones don’t work. Many of them come from this outstanding article by Susanne C. Moser and Lisa Dilling which I recommend everyone to read.

I’ve worked with science communication for almost 20 years. I’ve previously worked with medicine and health sciences and for the last seven years with energy sciences. At SINTEF, I don’t work with climate scientists but with climate technology scientists. There are differences between communicating about the climate, climate technology and health. However, they also have a lot in common: the desire to generate an awareness and understanding of what we’re doing, and to demonstrate how research makes the world better both for people, animals and nature so that the solutions we’re investigating are put into practice.

The article I mentioned above argues that climate communication is often unsuccessful because those communicating believe:

- The problem is a lack of information

- People are motivated by fear

- One size fits all

- Mass communication is effective

If we understand why we are unsuccessful, we can then find communication methods that do work.

A lack of information?

The information deficit model assumes that providing more information will make people more enlightened and lead to change. Unfortunately, it isn’t that simple. There is so much information out there about climate change and what it takes to do something about it. Despite this, we’re seeing more and more polarisation.

If we are to change attitudes and behaviours, we need to reach younger audiences. The Norwegian “Nysgjerrigper” project is an excellent initiative headed by the Research Council of Norway that teaches children and young people about science and scientific methods. The climate crisis is complex, and therefore it’s important that children and young people receive a sufficient and thorough education in climate science as well as insights into scientific methods and source criticism.

But what about the adult population? Studies have shown that some things that can get people to change their attitudes and behaviours are:

- Incentives (that people see the benefits of changing)

- Practical support for people to change

- Social support and positive group pressure

However, these are not communication measures, or something a climate scientist can achieve with science communication alone. They are typically political measures, decisions and incentives that can be combined with campaigns. For example, in Norway, we’ve become world champions in buying electric cars. Both financial and practical incentives have convinced many people to buy electric cards, which are combined with campaigns that have influenced them to want a zero-emissions car.

Another example is “panting” bottles and boxes (aka taking empty bottles and boxes back to the supermarket and exchanging them for money). Norway has the world’s most effective deposit-return system, as we return over 95% of what we can. Because returning boxes and bottles is so easy, and we are regularly reminded of its importance through campaigns, it has become a part of our daily life.

Another example of a Norwegian campaign (that is not politically initiated) is Blekkulf, a cartoon octopus. Blekkulf has helped children become advocates for the environment, and contributed to a positive group pressure that encourages parents to, for example, recycle plastic.

If we want people to make positive climate choices, it may be as easy as the average person seeing the benefits of changing through the introduction of incentives that lower the barriers to change combined with communication campaigns and a positive group pressure, for example, from your children telling you to recycle your rubbish. These methods increase the likelihood of behavioural changes.

Motivated by fear?

We’ve all seen pictures of polar bears crammed on top of a tiny ice floe as an illustration of climate change. Unfortunately, in recent years we’ve also seen pictures from all around the world that depict the consequences of climate change, such as floods and fires.

Fear communication can mobilise – of course it can. But if fear was all that’s needed, why don’t smokers stop smoking on the day they found out how dangerous it is? Cognitive dissonance – the discomfort we feel when our knowledge and actions don’t match – is something we all experience. That’s why most people go to the gym in January and not all year. The theory is that we try to reduce the discomfort of cognitive dissonance by, for example, trivialising our actions: “Is climate change really so dangerous for me? What I do surely won’t make a difference?”

A strong external pressure – such as the eradication of life on Earth due to climate change or an asteroid – can be so powerful and lead to such a strong cognitive dissonance that we choose to ignore the facts. Fear can lead to denial, apathy and alienation.

While it’s tempting to press the big, red alarm button, we must also remember that the climate is not necessarily the biggest priority in the average person’s life. People can have their own significant challenges in private, such as their health or finances.

Bjørn Samset from Cicero, who has made an incredible effort to share climate research with Norwegians for years, told Dagsnytt 18 that he tried everything he could to avoid “doomsday heralding” in his new book. According to Samset, if you play too much on feelings, you become a sideshow like Kate Dibiasky in the film.

So, what can we do? Should we pack everything in nice, neat packages for the public? No, we shouldn’t. However, risk communication and scary pictures should be combined with specific, constructive and collective solutions that normal people can relate to.

However, I don’t think we should be scared of appealing to people’s emotions – at least, not their positive emotions. Aristotle’s advice for effective persuasion, using rhetorical devices such as patos (emotions), etos (the speaker’s character) and logos (proof) are equally relevant today. Emotional communication is often a more efficient way to move people to action than sensible communication. In this sense, one can say that scientists are at a major disadvantage, as while they are particularly strong on ethos and logos, they aren’t as strong on patos.

Therefore, my advice is to speak to the heart and the head at the same time – without using fear. Appeal to positive emotions instead, such as interest and curiosity.

- I’ve also written a little about how we speak to the heart in this blog post.

One size fits all?

Not adapting the message to the receiver can, in the worst case, be excluding if it’s too complicated and seem condescending if it’s too simple.

One of the biggest obstacles to communicating complicated messages is the “curse of knowledge”: presuming that the other person understands everything you say.

When we’re in preschool, we generally speak the same language. Once we start school, we gradually start to develop our own interests and hobbies. Maybe you like playing Roblox? In that case, you can talk about it with other children who are also interested in it – while those who don’t play Roblox won’t understand what you’re talking about (such as poor parents like me).

Creating games in Roblox might lead you to becoming interested in programming. Maybe after focusing on programming throughout your schooling, you decide to study computer science at a university for six years and then spend four years working on your PhD. By the time you’ve finished your two-year Postdoc and become a professor, you’re rather specialised in your field. This will characterise your language and the way you talk about your work. In other words, there are maybe only a handful of people in the world who have the same level of expertise as you and actually understand what you’re talking about. This is the “curse of knowledge”, and it’s a pretty common diagnosis.

The medicine is simple: you must adapt your language to the person you’re speaking to, and you must speak to them through the right channel.

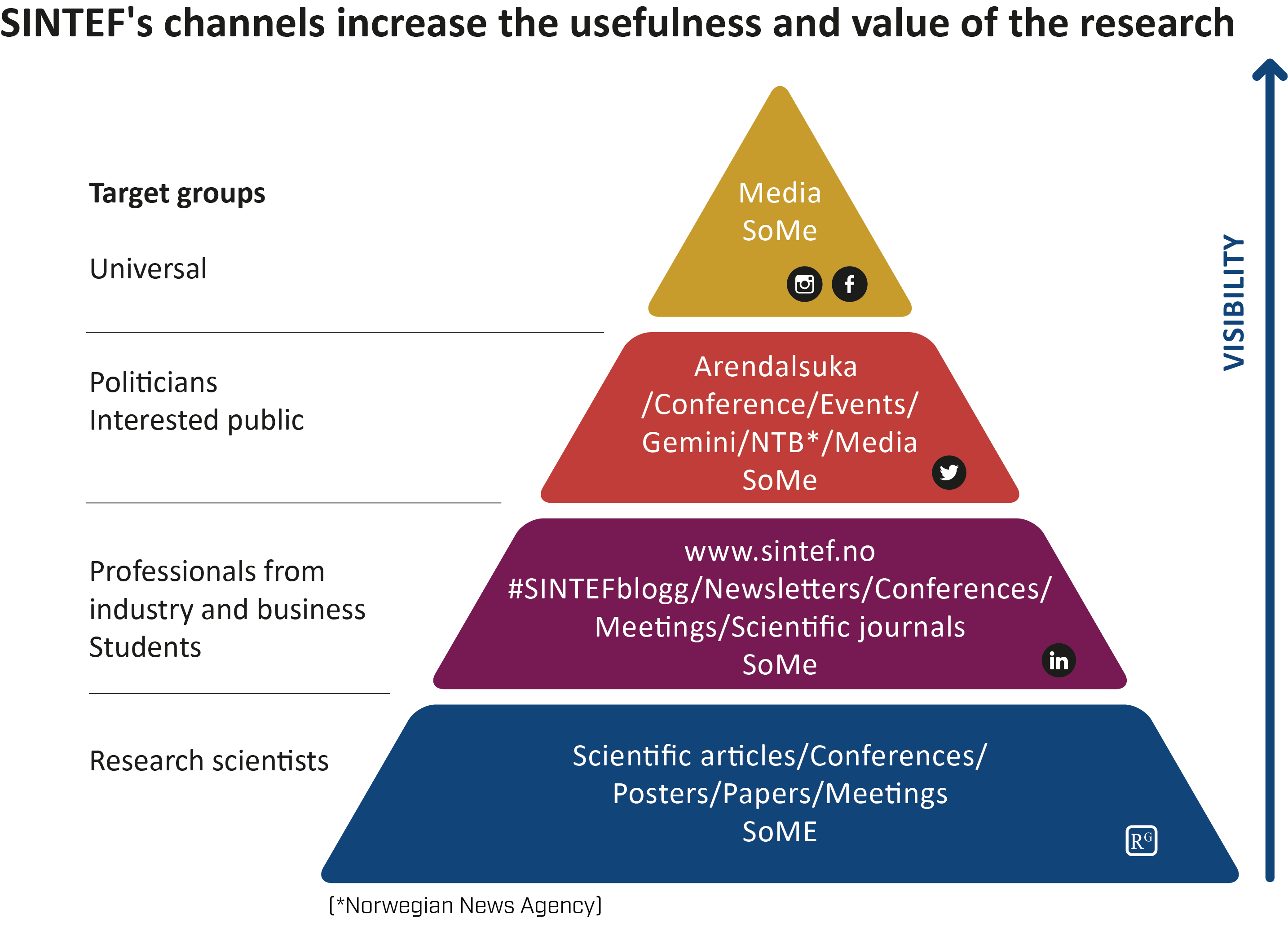

At SINTEF, we use the triangle above to illustrate different target audiences, and the suitable channels for reaching them. The thought behind it is that increased visibility in the correct channels for the correct target audiences will increase the value and use of our research. This blog you’re reading right now primarily has other industry and business professionals as well as students as its target audience. If it reaches more, that is a fantastic bonus.

It’s important to remember that you don’t need to speak to everyone at the same time. Sometimes, it’s more effective to choose the most important target audience and have a productive dialogue with just them. Once you’ve identified this group, you must find out:

- What they care about

- What motivates them

- What their values are

- What they think about climate change

- What prior knowledge they have

Is mass communication effective?

In an ideal world, you’d be able to reach everyone at once, including your main target audience. It would be extremely time saving and efficient if you could just do one mass media campaign, and then pat yourself on the back for a job well done.

Unfortunately, this is not always the case and extremely rare when it comes to science communication. Not only are there many actors vying for media attention, but attention from the users is also often low. This combination only reduces the potential impact of mass communication.

While mass media can be effective for setting a political agenda, in-person, face-to-face communication is more effective for persuading people to change their behaviour – but only if you trust the person you’re communicating with.

However, here’s the good news: scientists are among the professional group that people trust the most! This is truly a great starting point for successful communication.

- Trust in researchers: Trends in Science Communication During Covid-19.

Therefore, perhaps we should take a closer look at how commercial actors in particular work with micro-influencers? Micro-influencers promote various niche products and are perceived as extremely credible by their followers through blogs and social media. Even though this is not face-to-face communication, it feels more personal for followers than mass communication. We have thousands of clever climate scientists around the world, and I think they have significant potential for reaching wider audiences, such as their friends, colleagues and followers, if they used their social media (such as LinkedIn). I often see that our blogs get a much better response when they’re shared by the scientists themselves than when they’re shared in official organisational channels.

My colleagues who work with energy research use multiple channels to communicate in order to contribute to a knowledge-based debates on future sustainable energy solutions that are good for the planet. For example, on the SINTEF blog, we provide tips on how to ensure or burn wood in an environmentally friendly way. These are specific, constructive and collective solutions that the average person can make use of and are good for the environment.

However, we also advise politicians and businesses on how we can shift the energy system in a sustainable direction. We do this every year in connection with the Norwegian political gathering, Arendalsuka. In 2019, we challenged Norwegian politicians to invest in offshore wind now – and consider nature to a greater degree when developing offshore wind power. In 2021, we showed Norwegian politicians and businesses how the North Sea can be a platform for the green transition. We actually travelled to Glasgow in November to repeat this message about the North Sea at COP26, with an emphasis on international collaboration.

Is this really so difficult?

Can good communication save the world from the climate crisis or an asteroid on its way to Earth?

I’m optimistic that it can! When I was at COP26 in Glasgow, I saw over 100,000 people demonstrating in the streets for the climate. Many people, both young and old, have received the message. We still have a long way to go, but it isn’t hopeless.

However, we must still work to inform and engage as many people as possible. The methods that I’ve described in this blog for doing so can be summarised as:

- Combine information and incentives

- Motivate with solutions

- Adapt messages to target audiences

- Get more researchers to communicate

And who knows? If we learn how to effectively communicate climate research, maybe we’ll have more success than the scientists in Don’t Look Up in saving the world from an asteroid too!

Do you have any more tips for effective communication? Let us know in the comments below!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!