Co-authors: Eskil Aursand, Morten Hammer, Karl Yngve Lervåg, Gunhild Reigstad

During LNG operations, potentially dangerous events called Rapid Phase Transition (RPT) may occur. RPT events are sudden and explosive in nature, and exact prediction of if and when it occurs has eluded researchers for decades. SINTEF Energy Research has in the Predict-RPT project been researching RTP events since 2015, and in this blog we look into what causes RPT events and why we must continue to give them attention.

What is LNG?

While the term LNG is very familiar to people with work relating to the oil and gas industry, it may not be familiar to the layperson. LNG is an abbreviation for Liquefied Natural Gas, and while the engineering challenge is significant the principle is simple: Cool down natural gas to -162℃ to turn it into a liquid, which better fits into the ocean-faring carriers that take the product across the globe from producer to customer.

Natural gas itself is a fossil fuel which is mainly composed of methane and is gaseous under normal conditions. It is one of Norway’s most important exports, supplying 25% of the EU’s natural gas needs. An increasing fraction of natural gas is being transported in the form of LNG, due to the necessity of turning to more remote sources to keep the supply up.

What are Rapid Phase Transition (RPT) events?

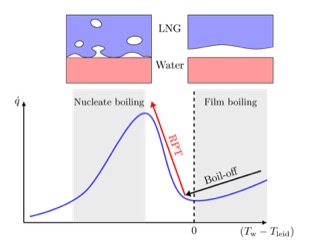

In marine LNG operations, either during production, transportation, or usage, there is a risk of LNG spilling onto water. As indicated in the figure below, the LNG (being lighter than water) will start spreading on top of the ocean surface while evaporating. While this often occurs without any further major incident, sometimes sudden explosive events occur. These are not explosions in the common sense, that is, there is no fire. Rather, these events are so-called vapor-explosions caused by abrupt and simultaneous evaporation of a larger amount of LNG. Since gas takes up a lot more space than liquid, a sudden transition will appear explosive. So why does this happen? While the issue is not completely settled, there is a general consensus.

Why do RPT events occur?

To understand why Rapid Phase Transition suddenly happens we must first understand why it normally does not happen. Since the LNG is very cold (-162℃) compared to seawater, a spill leads to an extreme boiling phenomenon called film boiling: The LNG spreads on top of the water mostly without touching it, that is, with a sub-millimeter vapor film in between the two. This vapor film works as insulation, which keeps the evaporation rate relatively low, and thus there is no RPT event.

The commonly accepted theory is that Rapid Phase Transition events are triggered because of a sudden breakdown of film boiling. As illustrated in the figure below, this occurs when the so-called Leidenfrost temperature of the LNG becomes high enough. The Leidenfrost temperature is initially too low for film boiling to break down, but this will change if LNG is given enough time to boil off.

In Predict-RPT, we are developing a large-scale spill simulator for RPT events. In parallel we have developed models based upon thermodynamic principles and data, that predict the sudden triggering and estimate the severity of the resulting vapor explosion. These models may be useful for engineers working to improve the safety of handling LNG processes.

Why LNG Rapid Phase Transition deserves attention

LNG has been transported in carriers at sea for roughly 50 years and has an excellent safety record. However, there are still good reasons to address the issue of Rapid Phase Transition risk:

- There is a record of actual unintended RPT-related incidents in the industry.

- Small accidents or near-accidents are not necessarily in the public record, so the risks may be higher than they appear to be.

- The LNG industry is currently evolving. The use of LNG as a marine fuel is projected to increase significantly, which will lead to more small-scale bunkering operations. The industry is also moving towards increased use of floating facilities for production, storage, offloading and regasification (FPSO/FSRU) in order to make remote gas fields economically feasible (see emerging FLNG vessels). These developments introduce additional scenarios for LNG leakage, as well as potentially more severe consequences. Such operations may not necessarily inherit the good safety record of the established LNG carrier operations.

Overall, in the interest of preserving the excellent safety record of the industry, no significant theoretical risk should remain poorly understood.

Recent progress on the thermodynamic prediction of LNG RPT risk and consequence is discussed in blog Using thermodynamics to predict risk and consequence of LNG RPT (Rapid Phase Transition). The models mentioned therein, and the details behind them, are described in our recently published academic article. Efforts to couple these models into the large-scale spill simulator are underway.

Acknowledgements and academic source:

This blog entry is based on the recent academic paper “Predicting triggering and consequence of delayed LNG RPT” (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2018.06.001) published in Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries. This publication is based on results from the research project “Predicting the risk of rapid phase-transition events in LNG spills (Predict-RPT)”, performed under the MAROFF program. The authors acknowledge the Research Council of Norway (244076/O80) for support.

Pingback: Using thermodynamics to predict risk and consequence of LNG RPT (Rapid Phase Transition) - #SINTEFblog

Pingback: Modelling liquid-on-liquid spreading during LNG spills - #SINTEFblog

Pingback: Reducing The Risk Of Delayed RPT Explosions From LNG Spills - #SINTEFblog