Imagine going to the grocery store. You want to buy some cod for dinner and then you see that they have a new brand labelled “zero-emission cod”. The cod was caught without any CO2 emissions on a zero-emission fishing vessel. Would you buy the zero-emission fish?

The ZeroKyst project

The interesting question here is whether or not it is even possible to catch fish with a zero-emission vessel. And if so, what are the reasons preventing us from having zero-emission fish in our daily lives? Within the ZeroKyst project, we want to develop such a zero-emission vessel for fishermen in Lofoten and throughout Norway. With research and pilot project development, we want to help overcoming existing barriers for investing in zero-emission fishing vessels. In this way, we aim to bring one of Norway’s most traditional sectors into the future.

The history of fishing in Norway

In the first months of the year (February to April), the spawning cod migrates from the Barent sea in the north down to the Norwegian coast and Lofotfisket takes place in the area of the Lofoten islands and the Vestfjord. Lofotfisket is the most important seasonal fishery in Norway and many fishers rely on it for their main source of income. Its origin goes back to the time of the Vikings, and it is still very popular and well known today.

Norwegian fishing today

Since the middle of the 20th century, the old traditional rowing and sailing boats have been replaced by newer fishing vessels and modern technology. However, certain regulations came into place, preserving the Norwegian small-scale fisheries, and up until today, cod in Lofoten is mainly caught with small fishing vessels of 10 to 15 metres in length. These vessels are usually family owned and provide the livelihood of the whole family. Often it is father and son or two brothers going out together to catch the cod.

The most used fishing gear on the smaller fishing vessels are gillnets. These are classified as passive fishing gear. This means that the fisher deploys the nets in the morning and then waits for the fish to swim into the net as opposed to active fishing gear like trawls where the net is dragged towards the fish. After a certain waiting period, the fisher retrieves the nets again and returns back to port each night.

Many vessels mean high emissions

As of today, Norway’s small fishing vessels are driven by one diesel combustion engine that constitutes the main power source on board, for both propulsion and operation of the fishing gear. With main engines installed that range between 100 to 300 horsepower (HP) for the smaller vessels and up to 500 HP for the 15-metre vessels, these vessels could be assumed to have just a modest contribution to the Norwegian national carbon emissions. However, fisheries and aquaculture are one of the main economic sectors in Norway and the total sum of all the vessels used within the fishing and aquaculture sector accounts for a total of 1.6-1.9 million tons of CO2 emissions per year. In comparison, all Norwegian domestic flights accounted for only 1.1 million tons of CO2 in 2019 (pre pandemic).

A zero-emission solution for fishing vessels

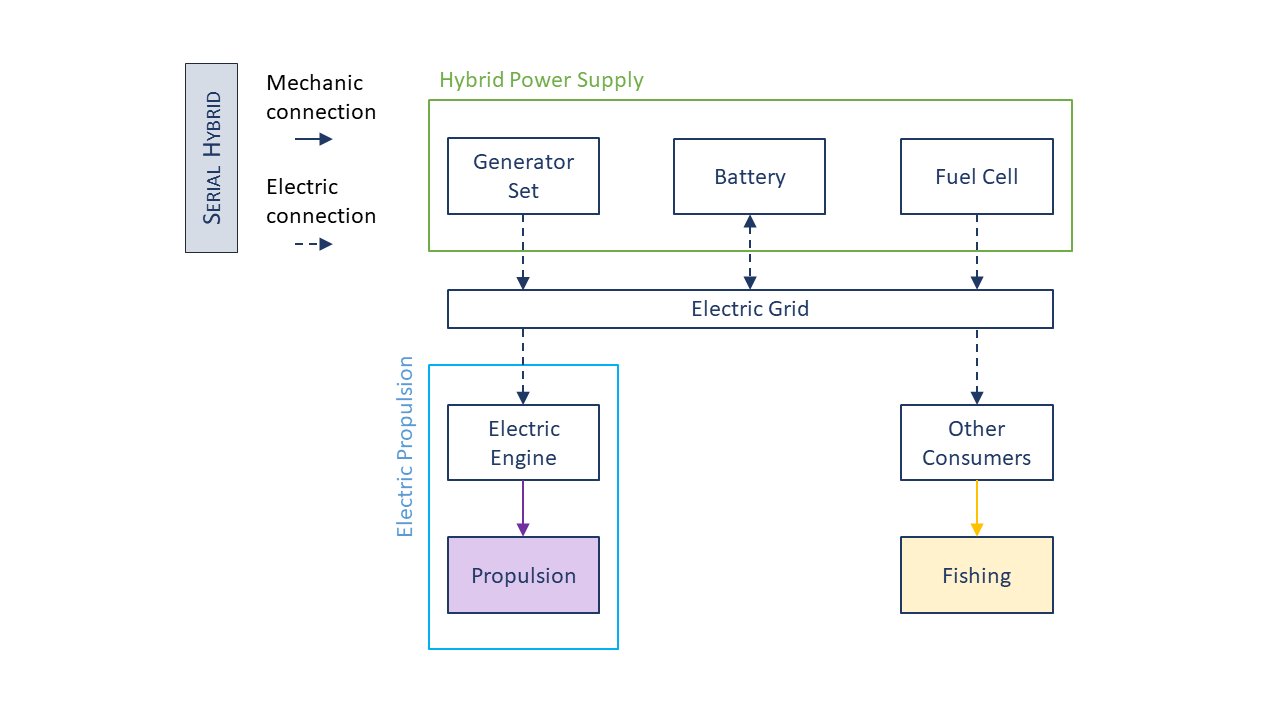

There are many options to decarbonise the Norwegian coastal fishing fleet. In the ZeroKyst project, we are focusing on electrifying the propulsion system. The electric propulsion engine and all other equipment on board will be powered by a diverse power system integrating hydrogen fuel cells, batteries, and a back-up diesel generator – in case the fuel cell cannot be used because hydrogen might not be available in each port yet. Drawing a parallel with the automotive industry, such a system can be described as a serial hybrid system or electric propulsion system with hybrid energy supply.

What is a fuel cell?

A fuel cell is a device that converts the chemical energy of a fuel, often hydrogen, directly into electricity through electrochemical reactions. It operates like a battery but can produce electricity continuously as long as fuel and oxygen are supplied.

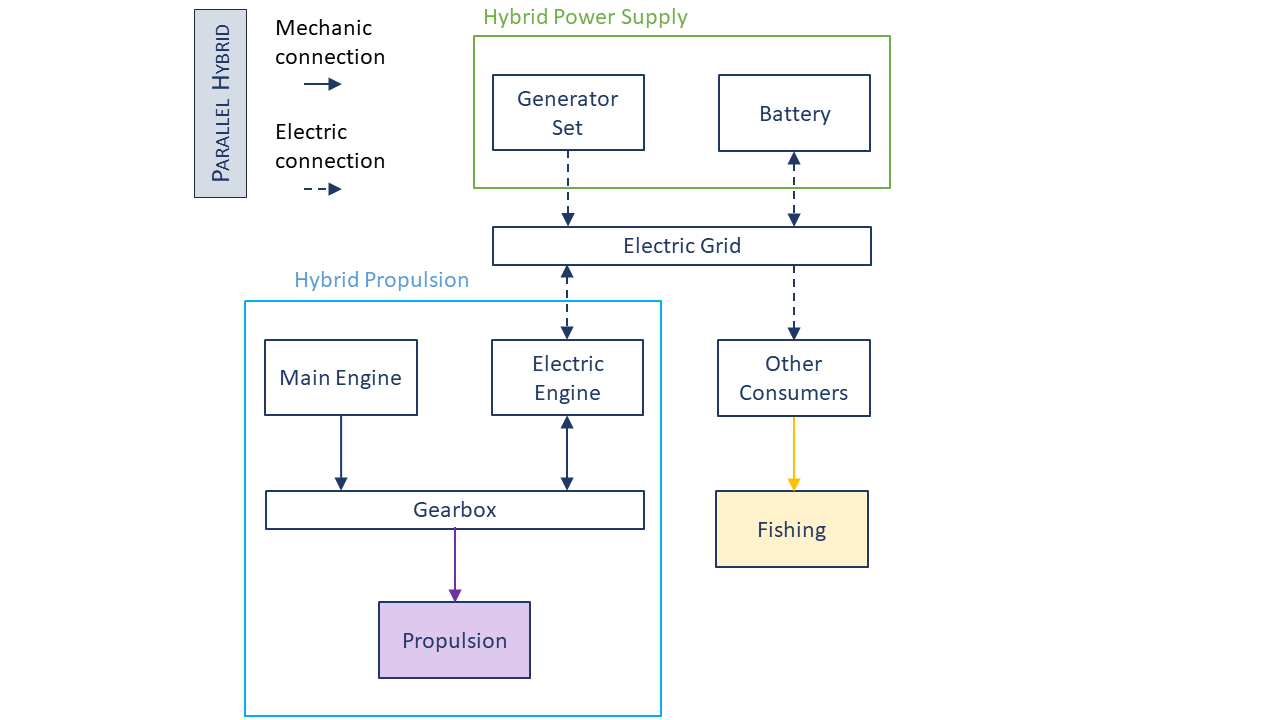

Parallel hybrid systems as a refit solution

The design and layout of a serial hybrid system is quite different from the conventional diesel engine setup used today, which makes it difficult to refit on an existing vessel. Therefore, we also propose a parallel hybrid solution to reduce the CO2 emissions of existing vessels in a way that is easier to implement. In this case, an electric engine will be connected to the gearbox, so that it can be used in parallel to the diesel main engine to propel the boat. Alternatively, the electric engine can also be used as a generator providing electric energy to the onboard grid. This system is completed by a battery pack that can be slowly charged over night while the vessel is at port.

A new fishing routine

The idea of this concept is that the fisher uses the diesel main engine only to transit at higher speeds from the port to the fishing grounds and back. During fishing, the vessel is sailing at a relatively low speed only using the electric engine. The battery pack provides the energy for propulsion and fishing equipment. In this way, the fishing process itself produces no direct CO2 emissions. Such a system will not only reduce emissions but also lead to a reduction in diesel fuel consumption, and in the costs they entail. In addition, this solution improves the working conditions as noise and vibrations during the fishing process are also reduced.

Concerns in the fishing community

So, why is not everyone fishing on a zero-emission or hybrid fishing vessel? To answer that question, we talked to many of the stakeholders involved in the coastal fisheries in Lofoten. Besides the fishers themselves, this includes ship owners and fish processing industries that are directly dependent on the success of a fishing day and on the amount of fish caught. In a wider context, harbours and infrastructure providers are in a supply-demand relationship dependant on the fishers. The same applies for specialised shipyards the fishers rely on for newbuild projects and repair work on their existing boats. On the other hand, the shipyards need enough customers to specialise themselves on coastal fishing vessels. In this way, the fisheries influence and form whole communities along the coast of the Lofoten islands.

Apart from the fishers and their representatives in fishers’ associations, as well as employees from a shipyard and infrastructure suppliers, we have also talked to people involved in the local politics. The consensus in these interviews was that economic reasons are the biggest barrier for zero-emission and hybrid fishing vessels. The investment is rather high, and the development of the fuel prices is uncertain. This includes the price of diesel as well as the price of electricity and hydrogen. For the latter two, fuel availability is another important reason that makes fishers reluctant to invest in these alternative technologies. This goes hand in hand with an uncertainty about the life cycle cost of the new systems as there is not yet enough practical experience with these systems and references available. This has fishers doubting the durability of components like the batteries and fuel cells, especially in the harsh environment of seasonal winter fishing in the north of Norway.

Related to this is a generally lower technical knowledge about these systems, and while most accept batteries as a mature enough technology known from widely used electric cars, they are more sceptical towards the hydrogen system. Practical questions have been voiced about the handling of hydrogen, also in the context of work that might have to be performed onboard and maintenance of the vessel. A low level of standardisation of new technologies like fuel cell and hydrogen systems and a lack of specialised rules and regulations for implementing them onboard a fishing vessel might pose further challenges.

Safety and environmental concerns

Another big concern of the participants in the interviews has been safety onboard. Fishing is one of the most dangerous occupations in Norway and there is a reluctancy to invest into new power and propulsion systems, as long as these have not been proven to be as safe and reliable as current systems. Finally, the fishers named uncertainty about the actual change in environmental impact as a reason not to invest in decarbonisation technologies yet. If they invest, they want to know that their investment will improve the footprint of their vessel also from a life-cycle perspective.

The path to zero-emission fish

Many of the concerns highlighted during our interviews can be traced back to an insufficient knowledge base about new propulsion technologies. This encompasses theoretical as well as practical knowledge that can be built up by research and successful pilot projects to increase the legitimacy of such technologies. In this regard, the interviewees, especially the ones representing the fishers and the shipyards, wished for more governmental and financial support, especially for the forerunners implementing and testing new propulsion systems. The entire Norwegian fishing industry operates on a system where individual vessel quotas allocate specific allowable annual catches to each vessel. The participants in the interviews suggested a kind of “green quota” giving a benefit in quota allocation and pricing to vessels with low- or zero-emission technologies installed.

Project ZeroKyst’s contribution

The ZeroKyst project aims to build a zero-emission fishing vessel to demonstrate that it is possible to bring zero-emission fish to the supermarkets. Furthermore, we are working on implementing more parallel hybrid systems in existing and new vessels. We also contribute to a better theoretical knowledge base with our research. A comparable life cycle analysis of the various alternative propulsion systems will give information about the real emission savings and can be used as a decision support when selecting a new power and propulsion system for a newbuild project or to refit an existing vessel. Safety and cost analyses as well as trade-offs between the separate assessments will complete a comprehensive sustainability assessment of low- and zero-emission power and propulsion systems for Norwegian coastal fishing vessels. In this way, we contribute with research but also with action so that we can all buy zero-emission fish at the supermarket one day. Now it is up to you. Would you buy zero-emission fish? And how much would you be willing to pay for it?

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!