Current cost estimates for floating offshore wind are higher than many other renewable sources, meaning significant cost reductions are needed for widespread deployment. Demonstration projects (such as Hywind Tampen or Kincardine – both in the North Sea) have proven that the fundamentals of the technology are sound, up to the size of turbines needed for utility-scale power generation.

These trial projects typically scale up reference or prototype designs that have existed for years to accommodate larger wind turbines. While this reduces design risk, re-use of reference designs is inefficient in terms of cost and material use. A reference design developed with the North Sea in mind will be heavier and more expensive than needed for a site in, for example, the Mediterranean Sea.

Earlier and realistic cost estimates

At the centre for research-based innovation, SFI BLUES, we have developed and expanded design optimisation techniques for floating offshore wind turbines, and other floating structures. These methods offer the potential to quickly determine trends and suggest optimal designs at the concept stage of project development, allowing developers to have more realistic estimates of costs at an early stage.

One or several optimised designs could then be used as jumping off points for further design refinement. In our recent publication in Marine Structures, “Gradient-based design optimization of semi-submersible floating wind turbines,” we present the first application of gradient-based design optimisation to semi-submersible floating wind turbines.

40 variables across 12 environments

Taking advantage of the capacity of gradient-based approaches, our tool optimises over 40 design variables describing the structural design and outer geometry of a four-column semi-submersible floating wind turbine substructure and tower. This represents a much larger design space than could be considered in previous studies.

The design is simultaneously analysed in 12 environmental conditions to evaluate constraints based on fatigue and extreme responses. We observe that tower designs are dominated by fatigue in the near-rated wind speed conditions and buckling in the rated wind and extreme wave conditions. Substructure designs are driven by the near rated and above rated wind speed conditions, depending on the section of the substructure.

The probability of these key wind speeds and the wave conditions associated with them vary widely across proposed sites: Even for sites with similar potential for power generation, there can be substantial differences in the design loads.

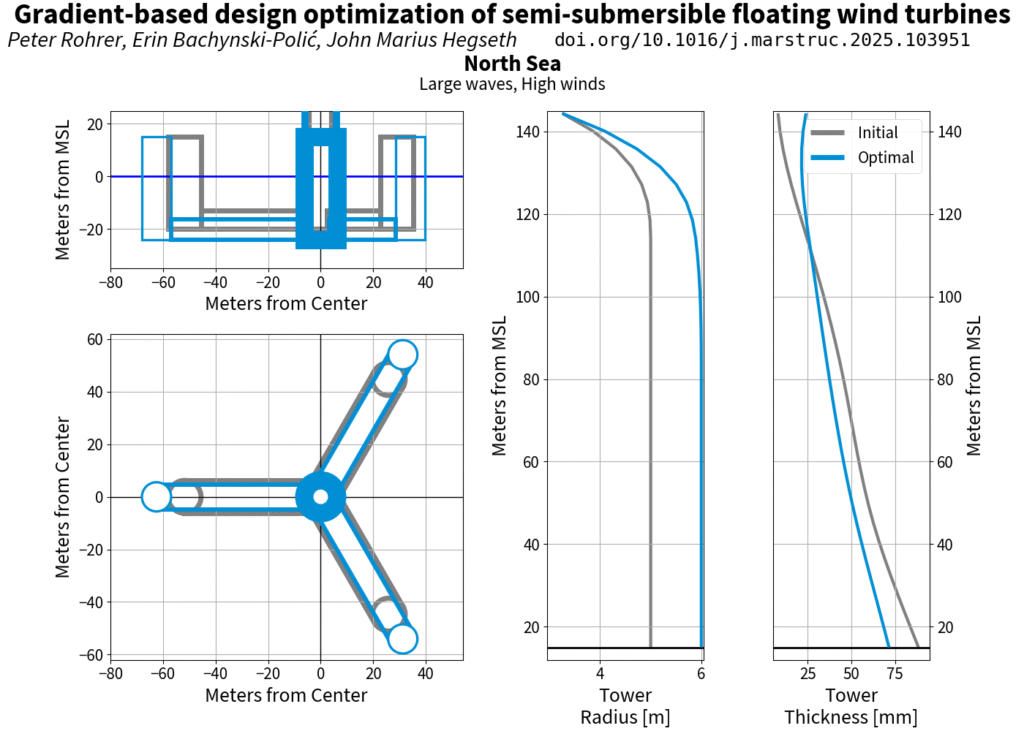

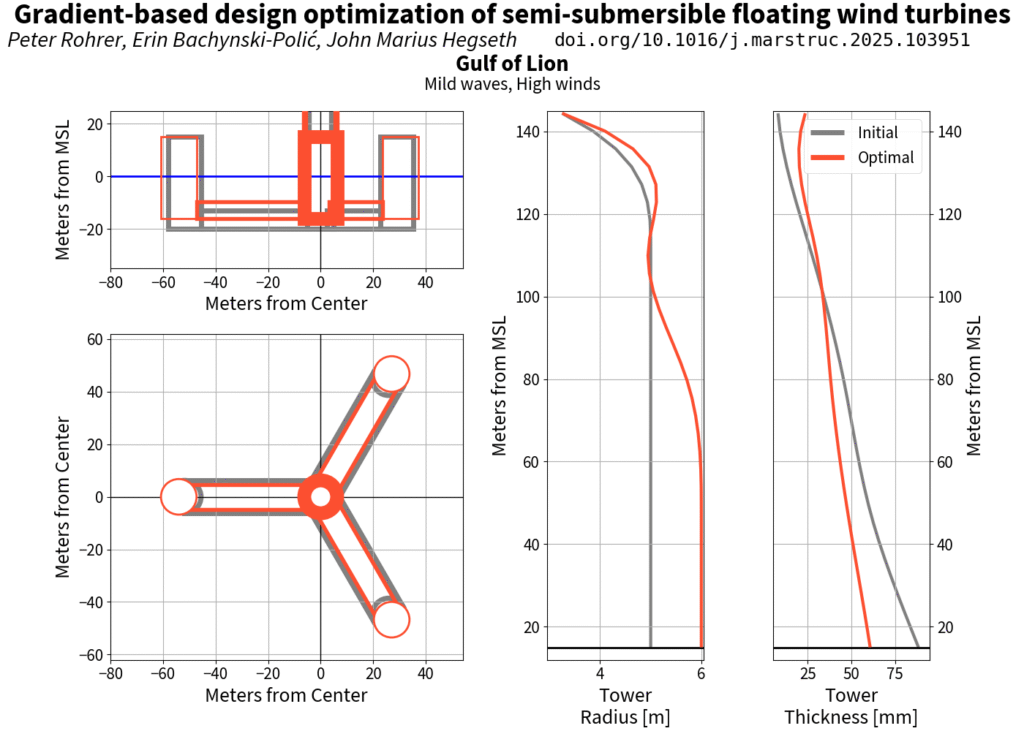

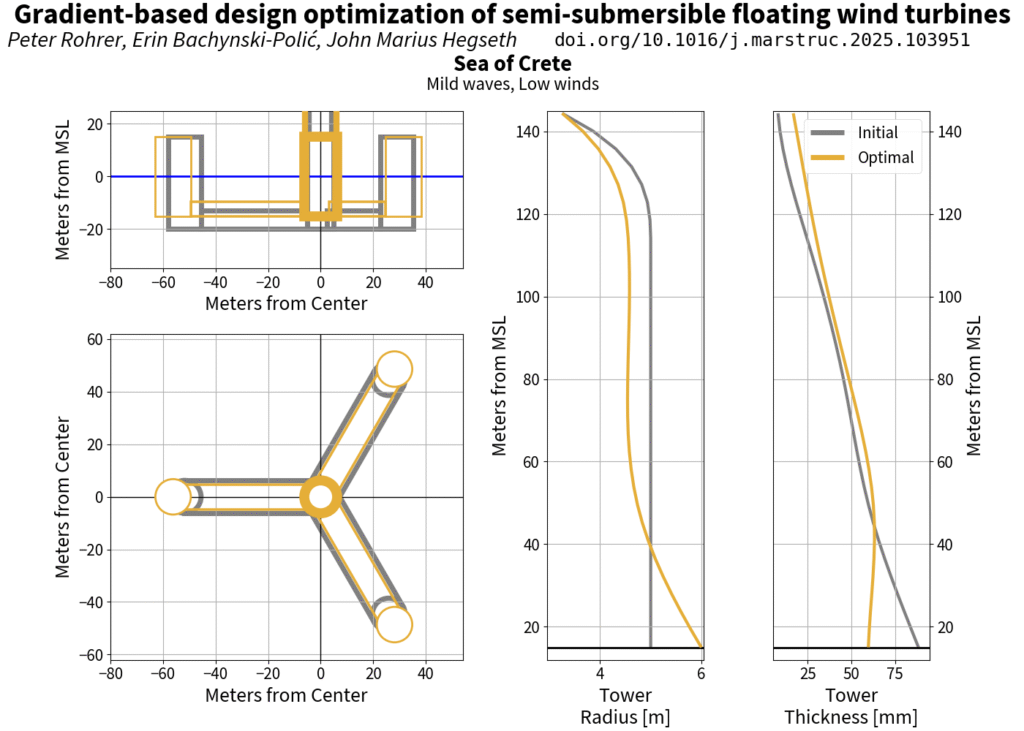

To further demonstrate the value of site-specific design, the same optimisation problem was considered in three sets of environmental conditions. Each set of conditions represented a proposed location for floating wind development: the Norwegian North Sea, the southern coast of France, and the near the island of Crete. The location in the North Sea is an example of a strong wind resource coupled with large waves. The south of France location has a similarly strong wind resource with milder wave. Finally, the location near Crete has a moderate wind resource and mild waves. The design for the harshest (North Sea) location was 70% more costly than the design for the least harsh (near Crete) location. Two of the locations had similar wind conditions but very different wave conditions. The optimal designs for these two sets of conditions had a nearly 30% difference in cost function, suggesting the potential for substantial losses by using a common design for the two sites.

Separate constraints, integrated impacts

These design optimisation methods developed by us in SFI BLUES provide a practical approach for comparing optimal designs for different locations, but also different designs at the same location. In another optimisation study described in the publication we showed that constraints on maximum tower diameter have significant effects on the design of a floating wind turbine substructure. Constraints on tower diameter are commonly imposed based on material handling or production capacity, but in this study, we show these restrictions have significant implications for the cost of the entire structure. This is an example of a design trend that is only possible to capture with an integrated optimisation method like we have developed.

What next

The gradient-based design optimisation tools developed in SFI BLUES are modular and built to be expanded on and adapted. Further improvements to these tools to include farm-level design impacts, controls co-design, and supply chain and manufacturing costs will allow for even more comparisons and trade-off studies. By enabling advanced comparisons in the earliest stages of the design process, these tools can be used by designers to understand and mitigate the drivers of increased cost for floating wind turbines.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!