co-Authors: ANDREA RAMIREZ (TU Delft) and ELDA RODRIGUEZ (TU Delft)

Update (2 February 2023): New research from SINTEF and TU Delft shows that CCS can result in significant CO2 reductions at a marginal cost

Results from a collaboration between SINTEF and Delft University of Technology (TU Delft), in connection with the Norwegian CCS Research Centre (NCCS), show that CCS implementation can have a minimal cost impact for end users while avoiding a significant amount of CO2 emissions.

100 seconds to midnight

On 27 January 2021, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists announced that the Doomsday Clock continued to read 100 seconds to midnight, citing human-caused climate change as one of the three main reasons for the current time. If we are to avoid disaster, technologies like Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) – the process of capturing CO2 and storing it safely deep underground – will be crucial to reducing our carbon emissions and setting back the clock.

However, CCS has often been criticised for being far too expensive as a means of reducing CO2 emissions. But is this really the case?

Costs and benefit potential

The impact of CCS implementation on industrial plants has been thoroughly investigated by several studies. For example, the CEMCAP H2020 project has shown that CCS implementation could increase the cost of cement by 50% to 100%, depending on the CO2 capture technology, while avoiding up to 90% of the CO2 emissions. Similarly, studies from the IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme (IEAGHG) have shown that CCS implementation on an iron and steel plant would increase the cost of steel by 20% while avoiding 60% of the emissions.

However, these studies do not aid our understanding of the cost impact of CCS on the end user. Most people do not buy cement or steel – instead, they buy the products that the cement and steel were used to build, such as houses or bridges. Cement and steel are just a part of the total cost of infrastructure, and their impact may therefore not be as significant as it is perceived.

Furthermore, we must consider the benefits that CCS provides for the added cost – in other words, the subsequent reduction in CO2 emissions. For example, if using CCS increases the cost of a building by 10% but only reduces its emissions by 3%, this would indicate that the benefit of CCS is not worth its cost in this case. However, if CCS decreases 50% of the building’s emissions for a 10% cost increase, a different conclusion may be reached.

Therefore, to determine the actual cost/benefit potential of CCS, we must explore its impact on end-user products and services, both in terms of cost and emissions reduction. This has been the focus of a collaboration between SINTEF and TU Delft.

Lake Pontchartrain Causeway

One of the case studies considered by SINTEF and TU Delft was the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway. The Causeway consists of two parallel bridges, one running north and one running south, across Lake Pontchartrain in Louisiana, USA. At 38.42 kilometres long, the causeway was listed as “the longest bridge over water (continuous)” by Guinness World Records in 1969. A toll of USD 3 or 5 is charged for drivers on the southbound bridge.

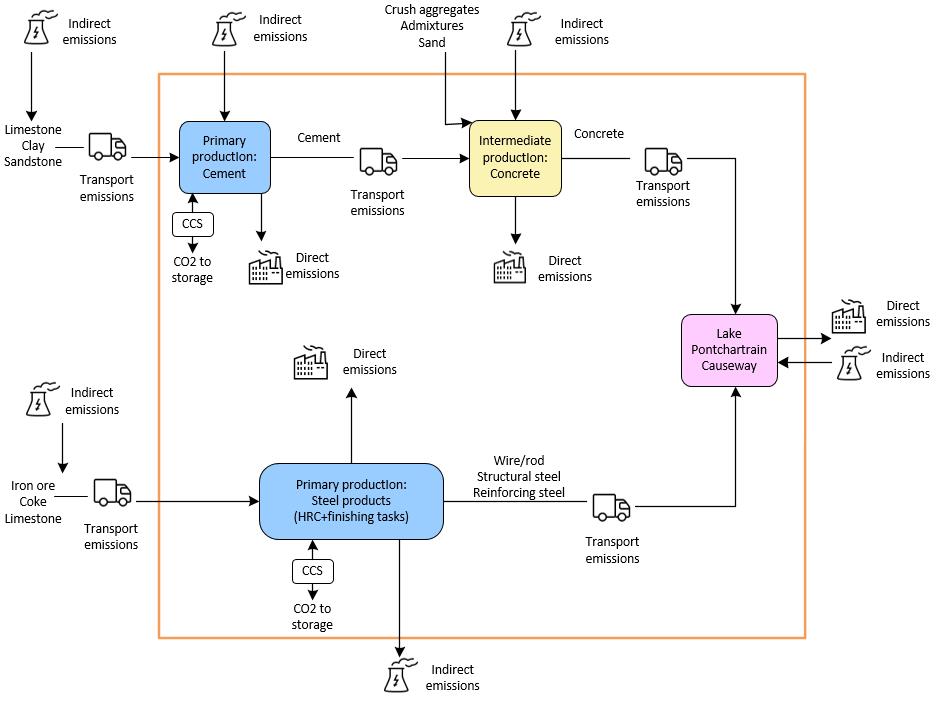

The case study examined the impact that CCS implementation on cement and steel production would have had on the bridge’s cost and CO2 emissions. Oxyfuel-based capture was considered for cement production, while MEA-based capture was considered for steel production.

When considering the complete value chain from cement and steel production to the bridge as an end product, CCS implementation only increased the cost by 1%. This is because the main drivers of the overall cost were related to other expenses, such as construction. Not only that, but CCS would also reduce the bridge’s overall carbon emissions by 60%.

Shifting the narrative

A 1% increase in cost is more than reasonable for a 60% reduction in carbon emissions. In the case of the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway, the 1% increase could be covered by a slight increase in the tolls already paid by the road user to access the bridge. In addition, the significance of a 60% carbon reduction cannot be ignored – particularly as the cement industry alone accounts for 8% of the world’s CO2 emissions. This case study illustrates how cities and governments could use public procurement of low-carbon materials to achieve their 2030 ambitions under the Paris Agreement at a reasonable cost.

So, is CCS really so expensive for end users? The results from this case study suggest otherwise. While more research is needed into the impact of CCS implementation on end-user products and services, we hope that this is the first step to a better understanding of the cost and benefits of CCS.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Magnus K. Windfeldt for his helpful comments and input.

Comments

These are excellent examples of cost effective climate measures! Very clear and transparent description! Will look for the detailed report!

Thank you very much Jan! We will share it once it is public

Since cement and steel are prominent raw materials in the construction of the bridge, any increase in their cost will proportionately increase the cost of bridge construction. You have mentioned that increase in the cost of bridge is just 1%. Since, there is a mention in your article that CCs will increase the cost of cement by 100% and steel by 20%, the above mention of 1% increase in cost of bridge may need revalidation.

Thank you for your interest in our work.

Yes there are indeed prominent material in the construction of a bridge however from the cost perspective there cost is dilute by the other cost of making a bridge such as the construction part.

A paper will be available next year presenting the complete evaluation and results.